Bringing in Livestock

Go to www.no-tillfarmer.com/mindemanngrazing to see how Mindemann is welcoming back commercial cows to his farm with some added help.

Alan Mindemann’s thirst for knowledge started at an early age. He was given a subscription to National Geographic when he was 6 years old, and his father always had lots of farm magazines around.

One day he read something about an Allis-Chalmers no-till planter. “I saw that and I thought, ‘You don’t have to plow,’” he recalls. “And I took it over to my Dad and said, ‘Can we do this?’ and he said, ‘Oh, it won’t work here.’ And I did that for the next 30 years, thinking it would never work.

“Then I got my chance to prove it works, and it does work really well — even in our area country, where it’s not the best farming country in the world.”

Guarding the Plants

Mindemann farms near Apache in southwestern Oklahoma, an area that is susceptible to erratic weather patterns — especially in the last 10 years, he says. Average yearly rainfall is about 32 inches, but can range anywhere from 16-50 inches in just a year or two. So far this month, he’s seen 7 inches of rain, whereas August tends to be scorching hot and dry.

Pan evaporation averages about 60 inches a year and can easily go up to 100 inches during major drought periods, such as the one that occurred in 2011.

Alan Mindemann

“We need those plants shaded and out of the wind, or they’re just not going to make it… And we’ve got to preserve all the moisture that we get…”

With plenty of frost-free days, Mindemann’s growing season is long enough that he can easily grow two crops a year, and nearly everything can be planted early or late. Despite that, he typically doesn’t have a set crop rotation, as precipitation and soil moisture often dictates what he can raise. He farms about 3,000 acres and plants 5,000 acres annually.

To date, he’s raised corn, soybeans, winter and soft red winter wheat, sesame, grain sorghum (milo), winter canola, pearl and foxtail millet, cowpeas, okra and mung beans.

Cover crops and forage crops can be raised just about the entire year, and he also raises non-GMO soybeans and mung beans for seed. While this might seem like a scattershot approach, Mindemann notes that when he started farming 20 years ago it was tough competing against established growers, so he’d plant specialty crops other farmers wouldn’t bother with.

“I got the reputation of being able to grow about anything. I’ll try anything,” he says.

Gauging Progress

Mindemann estimates 80-90% of the farmers in his area are raising a winter wheat monoculture and livestock in conventional-tillage systems, leaving many fields in bad shape with very little soil organic matter and low pH levels.

He says low pH, in the high 4s sometimes, is almost an epidemic in his area. Mindemann purchased his own application rig to do variable-rate applications of lime and gypsum based on recommendations from zone sampling.

When asked how long it takes to build soils up with no-till practices, diverse rotations and cover crops, Mindemann says it depends on the starting point. Some fields he’s rented have had massive amounts of tillage in terrain that can’t support it, leaving hillsides as sand rock as the soil eroded to the bottom.

“When I was growing up, the farmers who were considered good at the time now have land that is absolutely the worst,” he says. “The poor farmers who went out, let their fields grow up in weeds and disc it 2 inches deep and plant their wheat — their fields are the best now, health-wise. Because back then, the good farmers were judged by how deep and how often they worked the ground.

“I’ve had a couple of those poorer fields for 6, 8 years and they’re better than they were, but still aren’t very good,” he adds. “I tell my landlords, ‘I have to have a long-term lease because I’m going to build these farms up to where I can make some money at it. I’ve got to get my money back somewhere down the line. But when I’m gone, you’ll have a good farm.’”

But on his own no-till operation, soil organic matter has increased by about 0.10% each year on most farms, with some of them reaching 2.5% after starting at 1% or less.

Apache, Okla., no-tiller Alan Mindemann double-crops mung beans after small grains in summer and has had good success, noting the crop grows quickly and yields well with timely rains but still provides something if it’s dry.

Residue Matters

Mindemann says there’s no way he could be raising so many crops if he didn’t have no-till residue to shade plants from the elements.

Mindemann uses a Shelbourne Reynolds stripper head to harvest small grains and keep residue standing, which he says is critical to protecting his summer crops, planted form mid-June to Aug. 1. He drills crops directly into the standing wheat stubble as well, unless it’s canola, as that crop tends to favor less residue in its environment.

“We need those plants shaded and out of the wind, or they’re just not going to make it. And we’ve got to preserve all the moisture that we get,” he says. “When it rains, we need to catch it all because we never know when a rain might be our last one.

“My objective, on all these crops, is to keep them vegetative through August, the hot part of our year, and turn them reproductive in September when we start cooling off and actually getting some rains. And over the last 20 years that I’ve been doing this, it’s been a really successful plan.”

One example of Mindemann’s adaptations to weather challenges is with corn. Conventional wisdom in Mindemann’s area is that corn just can’t be grown, but he’s had success planting corn into killed bermudagrass, taking yields as high as 150 to 200 bushels an acre on some farms during favorable conditions.

“The trick to growing good corn in southwest Oklahoma on dryland is picking the right year to plant it,” he says. “We don’t rely on it for a crop every year.”

Mindemann raised non-GMO double-cropped soybeans after winter wheat in 2016 that yielded an average of about 40 bushels an acre, but some field areas hit 60-70 bushels. Typical yields in his county for dryland soybeans are about 8 bushels and 42 bushels for corn.

“So we get lucky once in a while. We plant low populations on corn and I only plant corn in a year that I think we might get some rain,” he say s. “And if it’s dry in the spring, we don’t plant corn. We just take advantage of the opportunities that present themselves to us.”

Mindemann also started seeding cover crops in 2005 as a means of keeping the ground covered so available soil moisture won’t evaporate and soil temperatures are kept at reasonable levels.

Seizing Opportunities

In addition to wheat, corn, soybeans and grain sorghum, Mindemann has long been experimenting with many specialty crops to bring in extra income if he can find a market for them. For the specialty crops he tries, Mindemann starts out planting a few rows in his garden, experimenting with different planting dates and observing their growth rate and characteristics.

“I’ll get an idea on what I can do and what kind of equipment it’s going to take to plant and harvest it,” he says. “Then we’ll try a little bigger plot and see how that works. Starting small is what I would recommend to anybody that really doesn’t know about a crop or doesn’t have somebody close by that can advise them.”

With all the specialty crops he’s growing, Mindemann admits there is a lot of time spent on sanitation in cleaning out augers, conveyors, bins and other equipment. He likes to utilize grain bags for storage to reduce the chances of cross contamination. None of the crops he grows go to the elevators, “and I’m fine with that,” he says.

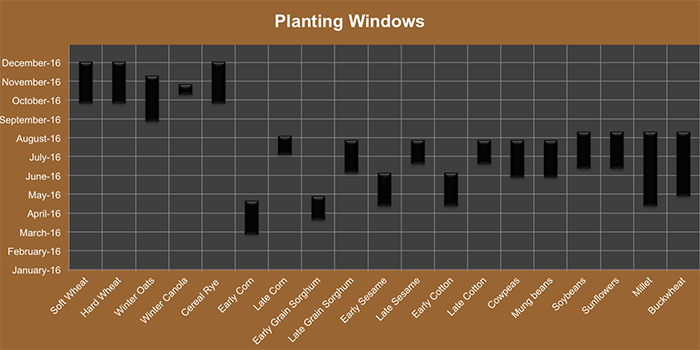

The planting windows Alan Mindemann has for the various crops he no-tills in southwestern Oklahoma. His growing season is long enough that he can often raise two crops in one year, although markets and weather affect what he plants from year to year. Click here for full size.

Here’s a breakdown of the specialty crops Mindemann raises on his farm:

Cowpeas. Mindemann seeds cowpeas after wheat, rye or oat harvest as a second or double-crop in mid-June to mid-July, relying on phosphorus applied with the small grains crops to provide some fertility for cowpea establishment.

He normally gets about 500- to 600 pounds per acre raising and swathing cowpeas to sell in the marketplace as cover crop seed. He also sees rotational benefits from the legume in the following corn or grain sorghum crops.

Winter canola. Mindemann participated in the original pilot program to raise winter canola in Oklahoma and he’s still raising the crop selectively.

“It’s a really good rotation for wheat and I’ve got several hundred acres of it this year, simply because it’s almost $8 a bushel and wheat’s $3-and-something,” he says. “It’s a really easy thing that a wheat farmer can do without any extra equipment.”

As hard as he tries, sometimes a field or two may not have enough residue left on the surface due to a crop failure, weather issue or some other disaster, and that’s where Mindemann prefers to seed canola, noting the crop sometimes struggles with high-residue environments.

Mindemann says this year’s canola crop overwintered well, but yields were disappointing due to unseasonably warm weather in February that forced the plants to bolt early and be stressed.

“I believe there’s a lot of work that could be done in shatter resistance and winter hardiness. It’s freezing out down here because of way it grows in the residue,” he says.

Sesame. Mindemann can seed sesame as both a double-crop in June after small grains or as a main crop in May, noting the planting dates are fairly close because the crop needs to be planted in warm soils. Sesame is an extremely drought resistant crop and it yields well, he says.

Mindemann’s noticed that feral hogs, which are a huge problem in Oklahoma, won’t go into sesame fields, perhaps because of the smell or being scratched by the plants. Although he didn’t go through with it, he recently considered planting a buffer of sesame around his cornfields to keep out the hogs, which can destroy 10-15% of a field.

Sesame will yield 900-1,200 pounds an acre in a good year, is easy to establish and uses very little water. Mindemann mid-row bands about 60 pounds of N between the 15-inch rows to get the crop off to a good start.

“No insects, birds or weevils bother it. And it’s usually twice the price of sunflowers in our country,” he says.

As is the case with many specialty crops, distance from processing can be an issue. The closest sesame processing plant in the U.S. is 50 miles away from Mindemann’s farm, but he’s established a 20-year working relationship with the firm. “I’ve grown seed sesame for them and we usually get the new varieties and try them,” he says.

Mindemann notes sesame is a contract crop and certain entities tightly control the distribution of favorable varieties that don’t shatter. He gets good returns at typically 0.28 cents per pound, but he did pick up some contracts from late 2016 there were 0.34 cents.

Proso, foxtail millet. Mindemann says he started growing a lot of this crop after a bird seed formulator 20 miles away called him many years ago and asked “You got any proso millet?”

“I said, ‘I can have some next year,” Mindemann recalls. “I’d never even seen it before but I knew guys in Colorado that grew it. And if they can grow it up there in the desert, I can grow it down here. So I grew a million pounds a year of proso for him. That was back when it was worth something.

“I won’t even grow it now, it’s too cheap,” he adds. “The guys in Colorado are basically giving it away. But it’s a great crop, easy and fast. I’ve planted early proso, harvested it, then planted grain sorghum and harvested it. We had two summer crops in one year.”

A few years ago, prices for foxtail millet were favorable and Mindemann grew a lot of it as well, raising some productive crops off very little rain after wheat harvest.

“We harvested a good wheat crop and then we had all this millet. But it’s just another instance of growing something that has a demand. Overproduction has killed the price for it.”

Buckwheat. Mindemann raises buckwheat for seed as a double-crop behind wheat. Although the seed isn’t worth what is used to be, he’s noticed some interesting effects in his fields for crops following buckwheat.

“In one field I had buckwheat on one side and double-cropped grain sorghum on the other side and harvested it. And then I planted it all to corn the next spring.

“I don’t know if the grain sorghum inhibited the yield or the buckwheat enhanced the yield, but we had two points more moisture and 30-bushel increase in corn on the buckwheat side,” he says. “So it’s one of those things that makes you go, ‘Huh.’ And makes you want to do it again.”

Mung beans. Mindemann has raised mung beans for many years, noting they’re easy to grow, mature quickly and will yield very well with a timely rain but still yield something if it’s dry. The planting window is mid-June to mid-August.

“There’s huge demand if you want to deal with the Chinese or the Taiwanese, and there’s very few people that are willing to take the risk to get the specialized equipment and everything you need to clean, bag, containerize and ship them overseas,” he says. “You can’t grow them just everywhere — Oklahoma is kind of the traditional home for mung bean production.”

Mindemann says mung beans can be swathed and picked up, or be desiccated and combined direct, but then they must be cleaned immediately. “There’s like a little knuckle on the stem by the pod that’s the same size as the seed and it will always be green and you’ll get it in the bin along with the seed,” he says.

“If you swath them and then let them dry out completely and then pick them up, you can store them without any problems. But the problem is finding a market for them. All these minor crops are about relationships. And the people that buy this stuff like to buy from the people they know. And right now, they got swarms of people trying to grow stuff for them.”

Grain sorghum. Mindemann says he grew more of the crop when prices were better, but currently he’s still double cropping some acres after wheat. Like many farmers, Mindemann has found the arrival of sugarcane aphids from the South has increased the difficulty and cost of raising the crop.

“We’ve grown a lot of white grain sorghum for the birdseed industry. We can grow some good milo, it’s just now it just takes more money to do it because of the aphids,” he says.

Cotton. This crop has good potential in Mindemann’s area but it’s heavily dependent on favorable rainfall, and weather patterns have been erratic in recent years. He’s found planting cotton into cereal rye helps provide some shade for the plants and protects seedlings from the wind and blowing sand.

He’s double-cropped cotton into stubble from 70-bushel wheat and yielded as much as 800 pounds an acre.

Okra. This was a new experiment for Mindemann, who last year grew 45 acres of it for seed production. He used his planter to plant it in 30-inch rows, and used a typical row head on his combine to harvest it. “I fiddled around with the settings a little bit and got them right and got a good, clean sample,” he says.

He said he used the Clemson variety that is popular for gardening, and the pods will get 10-11 inches long and will keep growing until a frost arrives.

Cereal rye. Mindemann worked in the certified wheat seed business for 12 years but got tired of filling out Plant Variety Protection Act forms and collecting royalties and everything else that comes with growing the seed.

So he started raising cereal rye for seed production, and to plant as a cover crop around his farm to fight against herbicide-resistant pigweeds, marestail and waterhemp. Ahead of planting corn or grain sorghum, he terminates rye with glyphosate, and the rye is also terminated and dead when it’s harvested for seed later in the summer.

“We grow a lot of non-GMO soybeans behind rye and have very, very few weed issues. Usually it just takes a burndown around the outside and in any water holes where we might not have had a good stand of rye,” he says. “It’s amazing how well a thick stand of rye will suppress weeds.”

Soft red winter wheat. Mindemann grows this for forage seed, after discovering a lot of ranches in Texas prefer this type of wheat because it produces more forage than hard wheat.

“And it’s a public variety which is a big deal, because traditionally the elevators just sold whatever came in and they were violating PVP rules. They can’t do that anymore. So I can guarantee them a public variety of a soft wheat that they want and it sells really well.”

He says this variety out of Georgia grows 40-42 inches tall. Ranchers will sometime mix in oats early in the year and ryegrass later in the year to stretch out their grazing season.

“This wheat is really uniform in between, so they’re not shifting cattle in the spring like that they would with rye or triticale. They can basically leave the same cattle on the same field all the way through,” he says. “They’re not scrambling to move cattle in because triticale is getting away from them.”

Perhaps Alan Mindemann’s most successful cover crop is cereal rye, which he raises for seed and as a cover crop ahead of corn or grain sorghum. “We grow a lot of non-GMO soybeans behind rye and have very, very few weed issues,” he says. “It’s amazing how well a thick stand of rye will suppress weeds.”

Keeping it Simple

Although there is plenty of residue to plant through each year with all the different crops, and residue with many different characteristics, Mindemann says he keeps the setup for his planter and drill fairly simple.

His John Deere air seeder is equipped with Thompson spoke closing wheels and “air dumps” as well.

“We only have a single run on this air seeder, so when we plant 3 pounds of canola and put 100-pounds of urea in mid-row banding, we’ve got to push it all through there at once,” he says. “The air dumps help take air out of the operation so we don’t blow the canola out of the rows.”

To plant corn, grain sorghum and okra, Mindemann uses a John Deere planter with Dawn SharkTooth row cleaners out front, set to knock down dirt mounts kicked up by feral hogs or knock down any tall residue in the way.

The planter also has one smooth and one Dawn Curvetine closing wheel to close the seed trench, and Mindemann runs a drag hose off to the side to apply nitrogen at planting.

For corn or grain sorghum, Mindemann typically applies a mix of 32% UAN, 10-34-0 and sometimes thiosulfate 1½ inches to the side of the furrow, and says he hasn’t had any germination problems with corn in spite of applying the liquid that close.

Post a comment

Report Abusive Comment