No-Till Farmer

Get full access NOW to the most comprehensive, powerful and easy-to-use online resource for no-tillage practices. Just one good idea will pay for your subscription hundreds of times over.

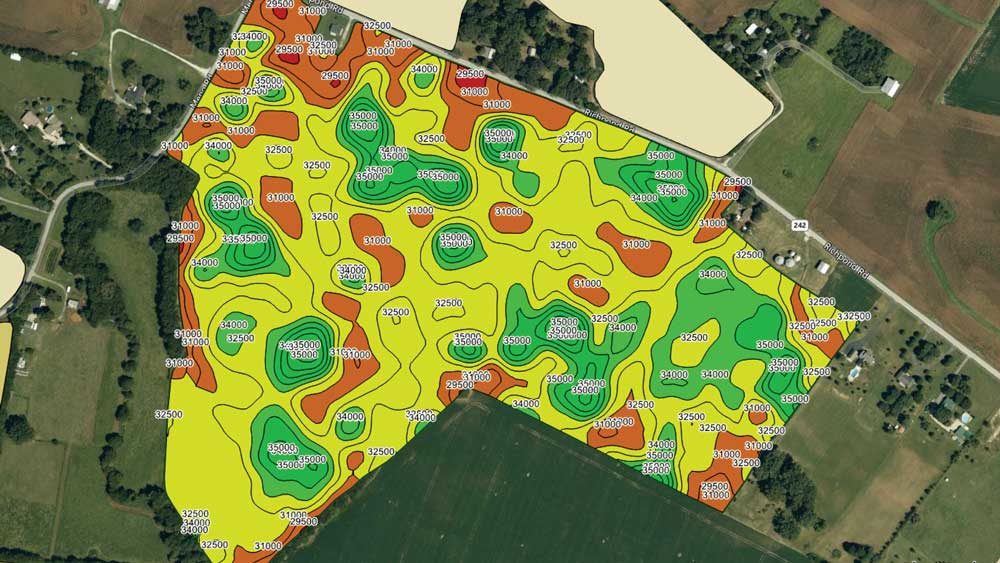

For decades Mark Chapman was aware of the differences within his fields.

“We’re known that we had high-yielding regions and lower-yielding regions,” says the Bowling Green, Ky., no-tiller. “Lots of times we knew why, but we weren’t able to do something about it.”

But that all changed once he was able to bring GPS onto the farm. With the ability to collect site-specific data, he can also take site-specific actions to address those issues using variable-rate technology (VRT).

At the 2021 National No-Tillage Conference, Chapman shared his strategy for variable-rating fertilizer and seed, and…