Pictured Above: No-tiller Charlie Hammer of Beaver Dam, Wis., planted corn in the spring of 2020 with a new closing system in beta testing from Martin Till. The new system is scheduled to be available for the 2021 planting season.

Never satisfied with the status quo, many no-tillers seem to always be looking for new solutions that will make them more efficient, improve profits and reduce the environmental impacts of their practices on the land. If there were a no-till motto, it might be “There’s got to be a better way.”

Beaver Dam, Wis., no-tillers Charlie Hammer and Nancy Kavazanjian epitomize this mindset, always testing new equipment and theories to tweak performance and achieve conservation goals on their 1,900-acre corn, soybean and wheat operation. They started no-tilling soybeans in 1985 and have been using no-till and strip-till techniques and the latest technologies ever since. Recently I had the chance to see some of the innovations they’re testing and/or implementing on their farm.

The first thing Hammer mentioned was a dual-stage closing wheel system from Martin Industries that is currently in beta testing. Tom Patterson, vice president of sales for Martin Industries, was on-hand and explained that the new closing system is designed to do a better job of closing the seed trench and get rid of air pockets, especially in light of the wet conditions many farmers have been dealing with in recent years.

“As the wheels run, it explodes that seed trench and sidewall completely. And it just explodes that dirt up against that seed. And the key is that the 5-inch press wheel that presses down and just takes all the air pockets out of it,” says Patterson.

In addition the system features a pair of slightly offset cupped razor closing wheels which “stitches” the seam together. Patterson says the teeth on the closing wheels are a little farther apart than previous models, which helps prevent them from getting plugged up with corn stalks or other residue.

The new closing system has been developed for both Case IH and John Deere planters and Patterson says the company is aiming at having the new systems available for the 2021 planting season.

Hammer is also testing out a new CTIS (Central Tire Inflation System) from PTG, a German company with distribution through Iowa-based Precision Inflation. He had the system installed as part of an overarching effort to implement controlled traffic on the farm.

“It’s part of a Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP) enhancement where you can’t traffic more than 25% of the field. With a 120-foot sprayer and a 60-foot planter, it works really well,” he says, adding that the only catch is that he’ll have to switch out his 12-row corn head of a 16-row model to make it all work out in the end. He has the CTIS on his sprayer as well, and he says the system, in conjunction with controlled traffic, has good potential to help reduce compaction considerably.

Conservation and environmental issues are a big concern for Hammer and Kavazanjian, as they are located on the Crawfish River watershed in southeast Wisconsin. Another project they’re tackling this year is a phosphorus (P) reduction program, an edge-of-field program that in the lab reduces P levels in the water by 90%. They’re hoping to get similar results in the field.

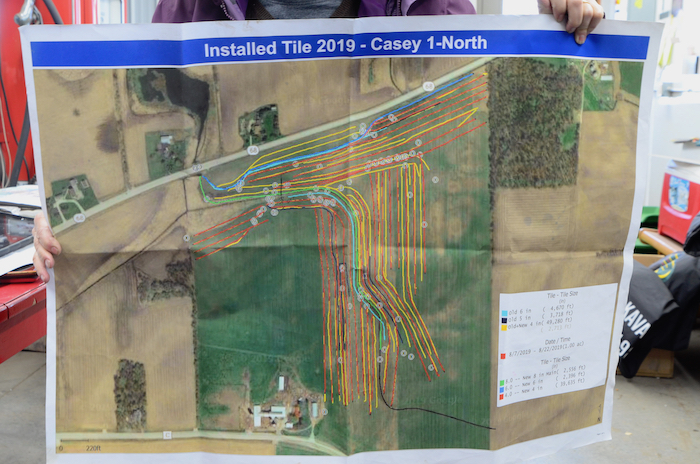

The field where they’re testing this concept had been tiled in the 1980s, so they replaced all the tile in the past year. All the water from the area will drain through the tile into a pit lined with slag that is a byproduct of the steel manufacturing industry in Gary, Ind. When the water passes over the slag, a chemical reaction takes place that precipitates out the P.

As part of their phosphorus reduction project, Charlie Hammer and Nancy Kavazanjian re-tiled the approximately 73-acre test field that drains into the Crawfish River watershed in Beaver Dam, Wis.

“If we can prove that it works and that we're taking the phosphorus out of farm drainage water, then Ag is not a problem anymore,” says Kavazanjian. “It’s not going to stop the algae blooms because we know there's a lot of what they call ‘legacy’ phosphorus still in the lakes. But we can say that as farmers, that we're doing our part to remove the phosphorus from the runoff.”

There are other potential upsides to this project, she says. Because manure has high levels of P, this technology could be impactful for dairy farms and the surrounding small communities.

“if we can really prove this, it has huge applications for water quality for lakes and rivers and then maybe another source of income for farmers,” she says.

“A lot of these small communities in Wisconsin have to take the phosphorus out of their water and it's a million-dollar upgrade to their sewer system. So instead of that, they could trade phosphorous credits with a farmer for $20,000-40,000, rent their land, pay for the install, a lot cheaper. The farmer gets some rental out of it and they get this huge benefit.”

Furthermore, she says theoretically the may be able to actually use the captured P and potentially spread it back on the land.

If this project is successful, Nancy intends to follow up with a nitrogen bio-reactor.

Post a comment

Report Abusive Comment