PROLIFIC SCAVENGER. Carroll, Ohio, no-tiller David Brandt typically likes to seed brassicas as a ‘trap crop’ to pick up nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P) and potassium (K) that corn plants may not have used. A 5-year trial he did in cooperation with Ohio State University found 250 pounds of N, 23 pounds of P and 230 pounds of K that were recycled by oilseed radish and present just ahead of spring planting.

David Brandt may like the nice, green color his fields take on after one of his cover crop mixes emerges. But he also likes to see another kind of green — the color of money.

This bottom-line view of cover crops became a habit starting in the 1970s and 80s, when he was working mostly with red clover. Through strip trials he found that it only provided him 60 pounds an acre of nitrogen (N).

“I’m kind of a greedy farmer. If I plant something, I want to make some money — so our cover crops have to make money also,” Brandt says. “I didn’t feel getting only 50-60 pounds of N was enough to justify what we were trying to do. We kept looking for things that would produce more N.”

Three-Way Rotation is Key

Brandt’s goal is to get 100% of his 1,150-acre farm near Carroll, Ohio, covered with some kind of cover crop. He’s hit about 90% of acres the last 3 or 4 years.

He’s turned this bottom-line approach to evaluating covers into a science. The last few years, in fields with 6- or 12-way mixes, Brandt says he hasn’t been applying any N for corn. And with only 50 pounds of applied N ,he’s raised 200-plus bushel corn when legumes were included in the previous cover crop mix.

“We can reduce our P and K applications by as much as 50% where we put peas and radishes in the field…”

“But you can’t reduce all of your applications the first year you’re going into cover crops,” he warns.

While many no-tillers have dropped wheat from their rotation because of limited profit potential, Brandt strives to keep at least a third of his acres in wheat because it allows him to seed a more diverse array of covers after harvest, which provides his farm more benefits.

“In a corn-soybean rotation you’re going to have about 4-6 weeks for your cover to grow, so it never gets to the size that I’d like to see it,” Brandt told attendees at the National No-Tillage Conference in January. “Within a wheat rotation you can seed covers in late July, early August and you’ve got August, September and October, and even some of November, for plants to grow.

“So after wheat we’ve got a much deeper root system, more nodulation, and I just think it’s a win-win.”

Species Benefits, Challenges

Brandt has worked with a large number of cover crops over the years, and they all vary in their ability to pull up N, phosphorus (P) and potassium (K) from deep in the soil. Here’s what he had to say about several covers:

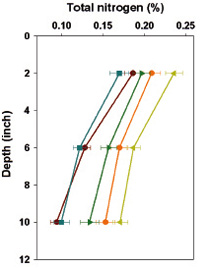

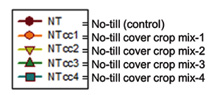

IT’S IN THERE. This chart shows how much total soil nitrogen (N) is available during August from cover crop blends seeded on David Brandt’s farm in a corn-soybean-wheat rotation. The red line shows no-tilled soils without covers, while the other lines show four different cover-crop mixes. Brandt says this shows there was ample N where there was a cover crop, and not enough N where there was just a corn-soybean rotation.

• Sweet Clover: This species of clover can put on 80 pounds of N in the soil, but it takes 1-1½ years to establish good roots.

“The roots will be as big as your thumb, probably 25-30 inches deep,” Brandt says. “You can’t plant sweet clover in August, kill it in May and expect very much — probably 15 or 20 pounds of N.”

• Crimson Clover: Brandt says this popular cover crop is native to North and South Carolina and he was once told it wouldn’t grow any farther north than Kentucky, but he’s made it work. With the potential to put about 75 pounds an acre of N in the soil, Brandt feels crimson clover has more nodulation than red clover.

• Faba Beans: Brandt says this cool-season plant doesn’t like the heat in August and hasn’t worked very well on his farm for yet another reason — it blooms in about 30 days.

“Once the plants bloom they’re taking the nodulation from the roots and trying to make flowers and seeds,” he says. “We don’t like to have our cover crops bloom because we’re losing nutrients.”

• Cowpeas: This warm-season legume does well in warmer conditions, seeded in August or September.

“We like to see warm-season legumes in our mixes for the diversity they provide. We have warm-season legumes and cool-season legumes in the same mix,” Brandt says.

He expects cowpeas to produce about 50 pounds of N per acre.

• Sunn Hemp: “We really like this plant,” Brandt says. “It’s an African plant, and tends to have large nodules and usually it doesn’t bloom for us. We can count on about 150-160 pound of N from sunn hemp.” He notes that it grows best in hotter summer temperatures.

• Hairy Vetch: This cover will stay green all winter and produce up to about 200 pounds of N per acre.

HEALTHY COVERS. David Brandt plants a variety of cover-crop mixes on his Carroll, Ohio, farm, including this six-way blend above that includes radishes, cow peas and Austrian winter peas. A radish carcass is visible, and there’s more pea residue below the wheat straw that helps build soil fertility.

“The biggest drawback,” Brandt says, “is you don’t want it in your flat, dark, black soils that are poorly drained. It’s a really voracious plant and you can’t get the sunlight down to help dry out the soils if they’re poorly drained in the spring.

“We find hairy vetch belongs on the very tops of our hilltops so the water runs away, the soil warms up, and you don’t lose any soil either.”

• Chickling Vetch: Brandt says some no-tillers like this species of legume, but on his farm it once bloomed only 25 days after seeding.

“When this plant flowers it moves all the nodulation to the flower and we only have about 25 pounds of N in the soil for corn,” he says. “So we haven’t used chickling vetch very much because if it doesn’t work the first time, I don’t give it the second shot. There’s too many other things that we can use.”

• Austrian Winter Peas: Brandt says this is probably his favorite legume cover crop because it’s easy to establish and relatively inexpensive at $0.60-$0.70 per pound.

“With a drill we can use 30 pounds an acre after wheat and count on about 150 pounds of N available for next year’s corn,” Brandt says. “It has a deep taproot and great nodulation.”

The taproot is important, Brandt says, because when he plants corn at 1½-2 inches deep, the first root comes out and often finds a nodule from that winter pea.

“When the corn is knee high and it’s time to sidedress, the roots go down to that 4- to 5-inch level, picking up that additional N to boost corn yields,” he says.

• Buckwheat: Brandt likes buckwheat as a cover crop because it can make P more available in the soil, by as much as 8-10 pounds.

PICKING UP ‘P.’ No-tiller David Brandt has found that seeding buckwheat has been very useful for making more phosphorus available — by an additional 8-10 pounds per acre in some cases — for the next year, noting the results he’s seen on his farm have been confirmed through soil samples.

“We picked up a farm a year ago that had a P reading of 6, which is pretty low for us. So in early spring, when we knew it wasn’t going to get colder than 32 F in the evenings, we planted buckwheat,” he says. “About 40 days later, we burned it off with Gramoxone and planted corn into it. That fall, we took a soil sample and we brought that P reading up from 6 to 19.”

• Sunflowers: This cover seems to have an appeal with “all of our older landladies that own farms,” Brandt says, as well as many high school seniors who like to use Brandt’s fields for senior photos.

But Brandt says he’s also seen sunflowers somehow help release micronutrients like zinc and copper in the soil.

“We normally have to put 5 pounds of zinc down when we’re planting corn. But 2 years ago, when we took our soil samples, we found the zinc levels came up by about 5-6 pounds, just because we were using sunflowers,” he says. “We didn’t see that change until we put sunflowers in our mix.”

• Cereal Rye: Brandt noted a study about cereal rye — that may also apply to annual ryegrass — that found the sooner rye is seeded, the more growth it gets and the better results in suppressing weeds and bringing up soil nutrients to the surface.

“I think rye collects a lot of N as a scavenger crop, and then releases it during July and August when the soybeans are making seed,” Brandt says. “Where we have rye in a field of corn fodder, our soybeans are usually up about 6-7 bushels per acre compared to no cover with just fodder.”

• Brassicas/Radish: Brandt typically likes to seed brassicas as a “trap crop” to pick up N, P and K that corn plants haven’t used. Brassicas are not only deep rooted, but tend to fumigate the soil and help reduce populations of soybean cyst nematodes, he says.

FLOWER POWER. The sunflowers used in covers on David Brandt’s Ohio farm aren’t just popular for high school seniors looking for a place to take photos. Brandt says he found sunflowers helped make micronutrients like copper and zinc more available to crops. “Two years ago, when we took our soil samples, we found the zinc levels came up by about 5-6 pounds, just because we were using sunflowers,” the Carroll, Ohio, longtime no-tiller says.

In a 5-year trial Brandt did on his farm in cooperation with Ohio State University, involving 20 total fields, researchers found the following amount of nutrients present in the soil, just before corn planting, that were recycled by oilseed radish:

- Nitrogen, 250 pounds

- Phosphorus, 23 pounds

- Potassium, 230 pounds

- Sulfur, 60 pounds

- Calcium, 150 pounds

- Magnesium, 20 pounds

He notes that Solvita tests were performed on soil samples taken from these fields to verify the amounts, and the results showed similar readings for the nutrients.

“I think you’ll agree that if we could find 250 pounds of N, 23 pounds of P and 230 pounds of potash, we can reduce nutrient requirements,” Brandt says.

What Mixes Can Do

Brandt has been working with cover crop mixes with anywhere from 4-14 different species, all geared at accomplishing slightly different things with his soils.

Some mixes he uses are more balanced — such as one that includes crimson clover, hairy vetch, winter peas, sunn hemp and cowpeas, providing both warm- and cool-season legumes to build N in the soil.

The benefits can be somewhat weather dependent. Brandt notes that in 2012 his cowpeas and sunn hemp fixed a lot of N because the daytime highs were 95-100 F, but last year, the same mix never got above 16 inches tall because of cooler weather.

“We had one day in August that got to 90 F, and our hairy vetch was about 3 feet tall, the winter peas were 4 feet tall and the crimson clover was 1 foot. That usually doesn’t happen in the heat of the summer,” he says.

On some fields, Brandt uses GPS guidance to seed radishes and winter peas in 30-inch rows, at a rate of ¾ of a pound per acre of radish and about 14 pounds for peas.

Brandt then plants corn right on top of the radish row, or an inch off to the side, having found the soil is about 2 F warmer where the radishes were seeded than where the winter peas are, and about 3% drier because radishes have a deep taproot to allow water to drain off.

“The radish does a lot of tillage. It will actually lift the soil 3-4 inches,” he adds. “It’s a great tuber and stores a lot of N, P and K from our soils. We can reduce our P and K applications by as much as 50% where we put peas and radishes in the field.”

Brandt sometimes uses oats and radishes together because both will winterkill, negating a herbicide pass in spring. He also likes to seed crimson clover and annual ryegrass together, as the ryegrass brings up P and K from the soil and the clover fixes N for corn.

“The problem we have on our farm with ryegrass is we don’t kill any plants until we plant our crops, so our ryegrass normally is 16-18 inches tall and a headache to get rid of,” he says. “If you kill it earlier, it’s not a problem. Well, I just hate to have something brown a month before planting because we’ve lost all expectations of improving the soil if there’s a dead plant on it.”

Brandt has a soil-building blend that includes Austrian winter peas, sunflowers, hairy vetch and oats.

“We try to have about 10,000-15,000 pounds of biomass on the soil surface,” Brandt says. “When we can do that we can change the organic readings in our soil by 0.25-0.5% per year.”

In addition to a 6-way blend that includes sunflowers, radishes, turnips, hairy vetch and crimson clover, Brandt has a 10-way blend that he says is producing about 23 pounds an acre of P and 150-200 pounds of potash. Even though this blend costs $40 an acre, the potential for reducing P and K applications over time by as much as 75% or, in some cases, 100%, can help pay for the cost.

THEN VS. NOW. Cardington clay is the dominant soil type on David Brandt’s Ohio farm, but decades of continuous no-till and seeding cover crops has helped him go from about 1,500 pounds of organic nitrogen (N) to better than 4,000 pounds of organic N. Organic matter has improved from 0.50% in the 1970s to 7.2% in 2013. “So that means I’ve got 40-50 pounds of credited N each year for the corn before I ever plant it,” Brandt says.

He has another 10-way, high-legume blend that fixes N and collects carbon dioxide from the atmosphere to transport it down to the roots to be used as N.

Brandt says high-carbon cover crops can be used where no-tillers are going to grow soybeans, because the soybeans will make their own N. But this can also get the carbon-to-nitrogen ratio out of balance, he adds.

One mix Brandt uses has an 80:1 carbon-to-nitrogen ratio, “but it does seem to help bring out beneficial insects and bring some P and K to the soil surface,” he says.

In this mix, the pearl millet, sunn hemp and cowpeas frost off in early October, leaving another 1½ months where cool-season legumes will grow, allowing the winter peas and hairy vetch to take over.

At the suggestion of NRCS conservation agronomist Ray Archuleta, in 2012 Brandt tried a 14-way mix on his farm that included sorghum-sudangrass, purple-top millet and many other species — at a cost of $50 an acre.

Some of the plants towered over him in September as he called up Archuleta to ask how the soils would dry out and warm up in spring, and how he’d be able to get his corn planter through the residue. Apparently, the risk was worth it.

“This blend changed our organic matter in this field a full percentage point in 1 year, which I couldn’t believe, and Ohio State couldn’t believe,” Brandt says. “It works best after wheat. You cannot believe the amount of nutrients there, and how loose that soil is come the following spring.”

Rejuvenated Soils

Brandt likes to share a comparison photo of the Cardington clay-based soils on his farm — one in 1971, where the soil had a yellowish appearance with 0.50% organic matter, and the other from 2013 where the soil is much darker and has 7.2% organic matter from continuous no-tilling and cover crops.

“In ’71, when I had a half-inch of rainfall, I could hold it in the soil. In 2014, I can hold a 3½-inch rainfall and not have anything run off from one rain event,” Brandt says. “We’ve gone from about 1,500 pounds of organic N to better than 4,000 pounds of organic N in the soil.

“So that means I got 40-50 pounds of credited N each year for the corn before I ever plant it.”

“I think you’ll agree that if we could find 250 pounds of N, 23 pounds of P and 230 pounds of potash, we can reduce nutrient requirements…”

Brandt says in fields with less than 5 years of cover crops, he uses 50% of what his agronomist recommends for applying N, P and K.

“With 5 years of cover crops and no-till we use no starter fertilizers — none, period. We evaluate the corn at 10 or 11 inches high by looking at leaf tissue samples, looking at the Solvita test, looking at what the SPAD meter tells us about chlorophyll in the leaf, and then if it needs some fertilizer, I’ll put it on.

“If it says there’s plenty there, there will be plenty there to make us corn. Those are all management tools we have to use.”

Erosion Costs Money

Additionally, Brandt notes that Ohio’s annual soil loss is about 6.4 tons of soil per acre, but with cover crops there’s a potential to keep nutrient-laden soils from running off and hurting your wallet.

“What leaves in that soil is P, K and organic matter. In 1 ton of soil a farmer will lose about $23-$36, depending on what his soil sample readings are, from erosion,” Brandt says. “Just imagine not losing that $30 a ton, and if you’re losing 6 tons, multiply that by 6,and that’s a lot of money.

“Now I don’t know whether our fertilizer companies would like us very well, but can you imagine how much you could reduce your inputs by not having erosion? And we no longer have to worry about algae blooms. We need to make sure that this soil’s not leaving.”

Post a comment

Report Abusive Comment