Every no-tiller in the Southeast knows of University of Tennessee’s (UT) “Milan No-Till Field Day.” The AgResearch & Education Center at Milan was established in 1962 on former Milan Army Ammunition Plant land. Today, nearly 700 acres of cropland are used for research.

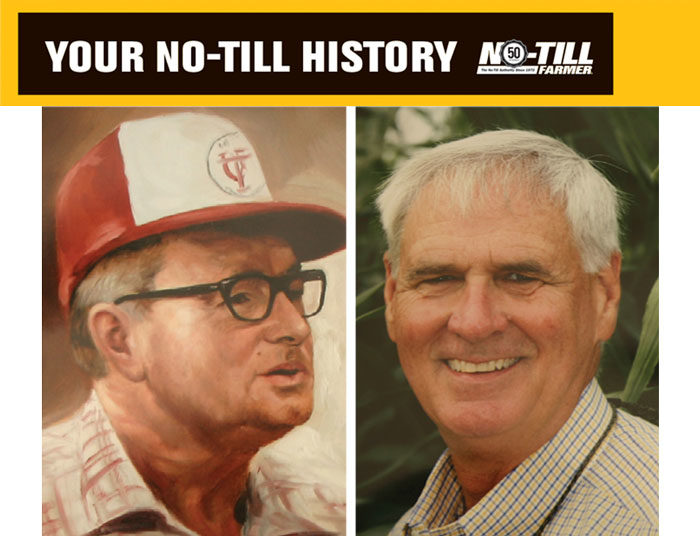

Thanks to the leadership of the first superintendent Dr. Tom McCutchen, a focus on no-till research to save Western Tennessee agriculture also led to no-till’s most influential field event in 1981. It brought at-scale, production-oriented no-till knowledge to the forefront where it could not be ignored.

John Bradley, a "No-Till Living Legend" and 1996 No-Till Innovator of the Year (Research & Education category, for his work at Milan) was there for the beginning of no-till in the state. At first, he was as an extension agent in Lake County, Tenn., near McCutchen's family farm. The friends collaborated often, including studying the no-till practice born in Western Kentucky the same year that UT Milan opened. After McCutchen died in 1983, Bradley was called on to oversee the center and Field Day.

No-Till Needed Now!

The tremendous soil erosion losses in Western Tennessee had McCutchen examining reduced tillage. “In the late 70s, West Tennessee’s 21 counties had the highest erosion rates in the nation,” Bradley says. “We were losing an average of 14 tons of soil per acre annually and a lot of fields were losing up to 80 tons.”

Bradley recalls a late 1970s “Save Our Soil” field day that highlighted terracing on a demonstration farm to combat soil erosion. “I asked what it cost to build those structures and the answer was something like $1700 an acre – which was 2-3 times more than the land was worth,” he says. “We knew no-till was what could solve the greatest problems.”

While other regions may have been dipping their toes into reduced tillage, Bradley says Western Tennessee jumped straight to no-till – before it was too late.

Early Years

McCutchen’s staff was working mainly through trial and error in those early days of no-till, says Bradley. He cited a list of variables of the process that must have overwhelmed everyone.

He and McCutchen realized early that no-till wasn’t just a new way to plant; weed control was a major challenge. “We didn't have today’s herbicides; we had to take what we had. Of course, there were all the fears of worsening insects and diseases on top of the lack of equipment. All were valid. Whatever the problem, we needed to figure out how to go over, under or around to address it.

Tye Co., Crustbuster and Great Plains were among the early manufacturers to introduce drills to no-tillers in Milan.

“Every barrier or objection that came up, we would take that and see what tools or modifications we needed to do to overcome that barrier. Then, we’d put that together as a system.

“There was work going on, but out of 15 researchers at Milan, only a couple wanted any part of no-till,” says Bradley. Plus, he and McCutchen were required to wear many hats – from agronomist and planter technician to weed, disease and fertility experts. “We played across the discipline lines enough to get the crops up. Because if you can’t get a stand, you can’t get the research. We had no choice but to be hands-on directors; it geared us to be more practical and application-oriented than we would have been sitting in the office.”

Later, when Bradley left for Monsanto to promote no-till cotton across the south, he received a compliment following a speech in Louisiana. “These farmers here could tell by the way you talked that you’ve laid under a planter before,” he was told. That was true from Dr. McCutchen too and resulted in a practical credibility that was needed for farmers to change.

Unsupported Initially

“The UT administration did not support the no-till research,” says Bradley. McCutchen located the no-till fields on the backside of the station to hide it from administrators’ constant view. “They didn’t believe no-till was worthy of the time and effort. They thought it was a radical, maverick way to farm.”

Steadily, McCutchen focused on a valuable group of researchers that he called his “TNT Team,” short for “Tennessee No-Tillers.” They became known for making research work on a 10-40-acre basis. “It earned the respect of farmers when on real equipment instead of plot equipment,” Bradley says.

Suppliers Welcomed

In those days, most universities were opposed to outside participation at research stations, Bradley says. “One thing that hadn’t been done at the time was inviting others in, and Tom did that. He got NRCS and other government-type agencies and started inviting industry in,” Bradley says, citing Allis-Chalmers (A-C), Chevron Monsanto, BASF, John Deere and Martin Industries. By letting them in, Milan got access to the first in herbicides, no-till planters and residue managers. “Suppliers would come and assist us or send us things that they thought might work.”

Bradley notes that this core group invested their time, products and money into the work there, which was the key. “The university didn’t put an extra penny in for the Field Day.”

First Field Days

McCutchen oversaw the annual Field Day in 1981 and 82. It was the first Field Day in the area that had ever let industry come in with exhibits, says Bradley.

With McCutchen’s death at 54 before the 1983 Field Day, Dr. Jim Brown (father of current director Dr. Blake Brown) served as interim director. Bradley was tapped for the superintendent post that fall. “When I took over in 1983, the UT Ag Vice President said, ‘You're not going to keep doing this Field Day, are you?’ I said, ‘I most certainly am and if you're telling me we've got to stop that, I'm not the man for the job.’”

The first Milan No-Till Field Day drew an overwhelming 1700 attendees and twice exceeded 10,000 in the 1990s.

The first Milan No-Till Field Day drew an overwhelming 1700 attendees and twice exceeded 10,000 in the 1990s.Soon, however, Bradley found the university softening on its opposition to no-till. That is until, a few years later, when he declared that all research at the center would be specific to no-till. Bradley maintains that the biggest mistake an extension or research station can make is to try to serve too many masters. No-till was the niche that Milan could fill, and it was meant to be exploited, not apologized for.

Promoting No-Till

“If you truly believe in something, your passion will drive you to tell the world about it,” says Bradley. “We had the bumper stickers, we had 35 mm slides and we had all extension agents talking about no-till and the Field Day.”

While Kentucky had a head start in no-till, Bradley says Milan outmarketed its northern neighbor. “We became more famous, I guess, but we got a lot of ideas out of Western Kentucky and out of Princeton, Ky. Howard Martin came down, and we learned a lot from Western Kentucky and adapted it.” Bradley says farmers learned more from Martin than anybody else in the demo fields.

Following a National No-Tillage Conference speech, John Bradley responded to an agronomist in the audience, who commented that a no-till cultivator was needed to provide a dust-mulch layer. Bradley’s reply was “Saying ‘no-till cultivator’ is like saying ‘virgin-whore.’ There is no such thing.” It was one time he was happy that his university bosses weren’t reading No-Till Farmer.

Bradley also found a willing partner in the community. “When I got there, this small town of 7,000 saw equipment coming through, but no one knew what we were doing. So we started opening the gates and inviting the community in. Because Milan didn’t have a festival or a claim to fame, the community focused on the Field Day.

“And we got tremendous support from the locals. A local caterer provided all the food. We added a no-till scholarship pageant, a tractor pull, a cotton fashion show. It became a community thing and everybody volunteered.”

Growth of the Field Day

“Everything we talked about or showed at the Field Day was research-based,” says Bradley.

Over time, the Field Day would have more than 20 planters running in a 60-acre field. “We had them plant 50 feet at a time and pull up and talk about their equipment. Bradley would see 300 exhibitors sign up at Milan, including nonprofits. But every exhibitor had to be tied to no-till in some way. “They told us they had more contacts to follow up than they could handle all year.”

Bradley will never forget the 1994 event, when the new dean witnessed the counters surpassing 10,000 visitors. “We had 8 tour buses from out of state conservation districts. Volunteers were shuttling visitors from the airport.” In time, the Field Day would attract attendees from more than 40 nations.

When asked for the defining moment for the success of the research and showcasing events, Bradley immediately answered. “It was 1987 when we required an ag economist on every research work plan. And it was not just looking at the numbers at the end but to watch what we were doing, taking measurements, and investing the time and effort.

“When studies showed lower costs in field and labor from no-till, they prepared the slides and data on the economics vs. conventional tillage. That was key; farmers saw the economics. The way to impact change is through the pocketbooks. They showed no-till brought comparable yields at a cost advantage and showed the results in dollars per acres.”

Bradley notes Brazil and Argentina’s explosive rise to embrace no-till, which was all about economics. “The American farmer could afford to be skeptical when the South Americans couldn’t.”

Click here for a historical photo gallery and a collection of personal memories about Milan No-Till Field Day. And click on the 2 links below for the "Innovators & Influencers" podcast and video from Blake Brown, who heads the University of Tennessee AgResearch & Education Center & No-Till Field Day.

This July 28

And what if McCutchen and Bradley hadn’t convinced the administration to pursue no-till research and the No-Till Field Day? It surely would’ve come, he says, but adoption in our area might've taken 2-3 times longer.”

The Milan Field Day is profound in no-till history. Director Dr. Blake Brown shares that Tennessee farmers practice conservation or no-tillage on 95% of their acres. Now held every other year, the Field Day is still going strong and will be held July 28. For information, visit www.milannotill.tennessee.edu.

Milan No-Till Field Day 2022 Participants

The 2024 No-Till History Series is supported by Calmer Corn Heads. For more historical content, including video and multimedia, visit No-TillFarmer.com/HistorySeries.

Post a comment

Report Abusive Comment