In 1993, Levi Neuharth’s father went to his banker and told him he was going to sell all of his tillage equipment to buy a sprayer and no-till drill.

That was the start of Prairie Paradise Farms’ move to a sustainable farming system. In the nearly three decades since, Levi and his wife, Crystal, have continued building on that no-till foundation by committing to the principles of soil health on their Fort Pierre, S.D., operation. In 2021, the couple received the South Dakota Leopold Conservation Award for their efforts.

Cover the Soil with Diversity

One of the primary ways the Neuharths imitate nature is by feeding their 2,300 acres of cropland and 3,000 acres of grassland with living roots and keeping the ground covered with a diversity of crops.

“It’s just as important to feed the livestock below ground as it is above ground,” Levi says. The Neuharths have grown several crops over the years, including oats, spring and winter wheat, barley, corn, sudan, millet, milo, teff grass, flax, lentils, peas and sunflowers. They warn no-tillers not to cheat their crop rotations because even lower-earning crops have an important role to play.

NO-TILL TAKEAWAYS

- A diverse cropping system helps keep the below-ground livestock fed and happy.

- Using a stripper header can help maintain residue cover on the soil between harvest and planting.

- The digestive system of dairy goats sterilizes weed seeds they eat, so they help reduce weeds.

“Peas might not be the most profitable crop we raise, but the wheat is usually a sure thing the next year,” Crystal says. “Having that nitrogen fixed really helps the winter wheat to be a good quality field each year.”

Expanding their crops has also allowed them to tap into some specialty markets. They’ve grown oats and milo for Grain Millers and have also done some work with Post. They’ve also sold to bird seed and cover crop seed markets.

Cover crops are another way they further diversify their plant species, and they grow a full-season of a mix for grazing. They aim to have at least five plant species in their mixes that vary in root types.

“With the diverse crop rotations and different roots, we’re improving water infiltration,” Levi says.

Designing a Full-Season Cover Crop Mix

The Neuharths’ cover crop mixes vary in species, depending on their goals for the field. Below are two examples of mixes they created specifically with soil health and grazing goals in mind.

Warm-Season Mix

Usually planted in June and grazed in the fall

- 1.8 pounds of sunflower

- 3.9 pounds of flax

- 3.8 pounds of BMR grazing cane

- 0.7 pounds of turnips

- 3.8 pounds of Waconia Cane

Cool-Season Mix

Typically planted in April or May, and grazed in the late summer to fall, depending on moisture, crop stages, etc.

- 1.5 pounds of red clover

- 4.5 pounds of ryegrass

- 1 pound of Winfred forage brassica

- 1.5 pounds of crimson clover

- 0.5 pound of Ethiopian cabbage

- 2 pounds of sudangrass

- 16 pounds of Goliath oats

One cover crop mix they first threw together included 0.6 pounds of sunflower, 12/3 pounds of BMR cane, 12/3 pounds of milo, 2¼ pounds of BMR sorghum-sudangrass, 1¼ pounds of radish and 1½ pounds of lentils per acre, which worked very well for cattle grazing. They were able to feed 145 cow/calf pairs on 36 acres of the mix for 16 days.

Now they have two full-season mixes, one that primarily contains cool-season species for grazing in May, and another that includes more warm-season plants to graze between October and November.

One lesson they’ve learned in creating cover crop cocktails is to ensure the species will provide good residue cover.

“It’s one of our keys to keep the crop residue from the previous crop around until the next crop that we’re growing canopies,” Levi says.

This is also why they limit the amount of brassicas they use in their mixes to around 2-5% because they realize just how quickly brassica residue will decompose.

Another key to making their residue stick around long enough is to use a stripper header. They try to cut as many small grains as they can with it, including oats, winter wheat, spring wheat and flax, because it will just strip off the heads and leave the rest of the crop out there, Levi says.

“If you have down or lodged crops, sometimes it will suck that crop up and stand it back up so you have better armor out there and it’s not just a mat.”

“If you stimulate it before it’s flowering, it’s more likely to get more tillers. That’s how we’re increasing our grass production…”

Integrating Livestock for Soil, Income

Cash and cover crops aren’t the only way the Neuharths introduce diversity. They also own a variety of animals, including horses, dairy goats, chickens, peacocks and pigs, and they custom graze cattle.

And they don’t just diversify in the types of animal, but also in breed. For instance, they have both heat-tolerant and cold-hardy chicken breeds, and “every breed there is of dairy goats,” Crystal says.

The livestock improve the health of their land while also providing additional sources of income.

The chickens are free-range, so they help control the weed seed bank, contribute fertilizer and are great for foraging insects, particularly grasshoppers. The Neuharths aim to keep them laying year-round and sell the eggs.

And while the Neuharths originally started raising dairy goats because their youngest son has a dairy allergy, they’ve since learned they provide a lot of benefit to the soil, too. Their digestive tract sterilizes any seeds they eat, so they help reduce weeds, which has made them great for grazing waterways.

They will also eat plants that are less desirable to cows.

“Some people think that the cows and goats will overeat, but they actually select for different things, so they complement each other very well,” Crystal says.

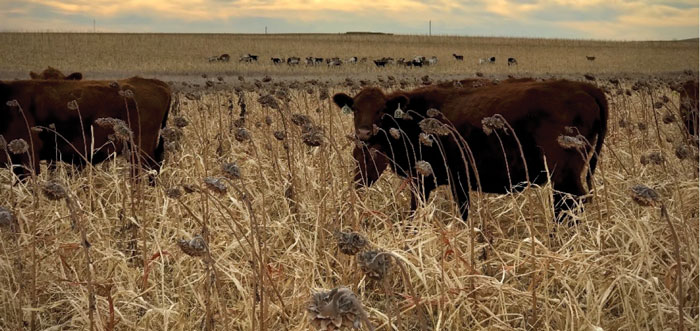

GRAZING COMPANIONS. The Neuharths graze both cattle and goats (in background) and say that they complement each other well because they’ll eat different species of plants. Goats are also great for grazing weedy areas because their digestive systems sterilize seeds.

While they don’t sell raw dairy goat milk for human consumption due to the laws in South Dakota, they’ve found other profitable avenues for it. They’ve finished pigs on it, and it can also be used to feed puppies or calves that have lost their mother. They often market their dairy goat kids to rodeo programs for goat tying, but they’ve also sold goats to backpacking hikers and hobby farmers.

The cattle are the only animal the Neuharths don’t own, but custom grazing them gives them the best of both worlds because it’s a great source of income with low risk.

They get the cattle around the end of May or beginning of June and try to keep them until the first of November. They don’t have to put hay out for them or feed them in the winter, so it’s less labor. And it allows them to get the cattle on cropland and make better use of their grassland through rotational grazing.

Sustainable Grazing Rotations

The Neuharths have been rotational grazing since 2010, a practice that promotes forage production and quality, soil fertility and water infiltration.

They have 3,000 acres of grass they try to get the livestock through. This includes their goats as well as 300 cow/calf pairs, which they split into three groups to rotate. They aim to start and stop in different areas on the farm so they can keep the diversity in warm- and cool-season plants. They also try to document fixed locations with photos to observe changes that are taking place, to see the new diversity of plants growing and how areas are recovering, so they can give them the rest they need to recover.

They’re about to start their fourth year of biologically effective grazing, a concept they learned from North Dakota State University range scientist Lee Manske through Lealand Schoon, an NRCS area range management specialist.

Crystal explains that the process starts by rotating livestock through a number of paddocks — three to six is ideal, and the Neuharths use four — within 45 days. Take 45 and divide it by the number of paddocks to determine how long the livestock should be in each paddock. Grazing should start around June 1, but no earlier because the native grasses need enough time to hit the 3.5 leaf growth stage before being grazed.

“It’s just as important to feed the livestock below ground as it is above ground…”

After 45 days, those paddocks get 45 days of rest before going into the second rotation, which will last 90 days. They stop grazing on those paddocks by Oct. 15, sometimes sooner if it’s been too dry, to ensure they don’t overuse the grass. After Oct. 15, the livestock are grazed either on cover crops, grassy areas they haven’t covered yet, or sometimes corn stalks or milo stalks.

The aim of this grazing system is to only remove 25-33% of the grass in the first rotation.

“Generally the grass only produces two to three tillers a year,” Crystal says. “The goal behind it is if you stimulate it before it’s flowering, it’s more likely to get more tillers. That’s how we’re increasing our grass production — through tillering.”

The Neuharths hope to get 6-8 new tillers a year if they’re stimulating the grass before it flowers.

Other benefits of biologically effective grazing is greater photosynthesis, improved water infiltration, increased plant diversity and keeping living roots going as much as possible.

“You’re going to stimulate the plant and then it’s going to take off and grow while it rests and recovers,” Crystal says.

Soil First

With everything the Neuharths do, they prioritize the soil by protecting it and feeding it. And even though their soils are a heavy clay that can be challenging to work with, their system is paying off. Levi recalls one year where rain created a lake in the middle of a milo field. But their soil structure held up, and they were able to combine right through the water.

“We go by the motto that if we have healthy lands, we’ll have healthy animals and healthy families,” he says. “We’re trying to let our lands work for us instead of us trying to make the lands work.”

Post a comment

Report Abusive Comment