The dry conditions that have prevailed over much of Kansas since the fall of 2017 have left some wheat growers with relatively dim prospects for grain production for the summer 2018 harvest. An alternative use for that wheat is as a forage crop — silage or hay — which may still have considerable value at a time when pasture grazing prospects and hay supplies may be uncertain. This article briefly looks at some issues producers should consider as they contemplate their options for their drought-stressed wheat.

Wheat silage and hay can both be valuable feedstuffs for cattle producers. Wheat harvested at the dough stage should contain approximately 56-62 percent total digestible nutrients (TDN) and 8-11 percent crude protein, on a dry matter (DM) basis. Wheat silage and hay may be used in the diets of feeder cattle, calves, replacement heifers, and beef cows. However, if the wheat is harvested post-heading, producers should grind the wheat hay if the variety has awns, since awns can cause health problems if fed unground.

Producers looking at these alternative uses for their wheat crops should also consider their options for marketing each type of feedstuff. For those who do not have their own cattle to feed, prospective demand for either silage or hay from nearby livestock producers could play an important role in their decision. Hay is more flexible in that it can be hauled farther and may be of use to a wider potential clientele.

Finally, insured wheat growers should check first with their crop insurance agent regarding insurance requirements to document potential grain yield losses before harvesting a forage crop. If producers believe they would have low grain yields and otherwise be entitled to an insurance indemnity, they may be required to leave small areas of uncut wheat to provide a way to estimate grain yields for the insurance loss calculation. Insurance agents can also inform producers of any other restrictions which may apply.

Making Wheat Silage

Timing is a key factor for making small grain silage. Small grain forage yields and feeding values depend heavily on the stage of maturity at the time of harvest (noted here). The optimal moisture level for ensiling small grains is 62 to 68 percent. Moisture levels above 70 to 75 percent can cause excessive seepage and undesirable fermentation (noted here). At lower moisture levels, the silage may contain more hollow stems and result in excessive air entrapment. This possibility means that small grain silage should be chopped finer than corn or sorghum silage. Timing is crucial in obtaining these target moisture levels. It is often more of a challenge to put up small-grain silage with adequate moisture if harvesting at soft-dough, which requires little drying time between swathing and chopping, while putting up silage in the boot stage may require some drying time between swathing and chopping. Carefully monitor moisture content when swathing and chopping. Wheat maturity can advance quickly, so producers with significant acreage to harvest may consider whether to begin while the grain is still in the milk stage, when moisture content is typically 65 to 70 percent.

Information from New Mexico State University Extension indicates there are actually two schools of thought on the timing of small grain silage harvest. The more conventional perspective aims for ensiling during the late-boot/early heading period because energy and protein are optimized. The quality may be high enough to use for lactating dairy cows. The second perspective argues for waiting until the soft-dough stage; while this later harvest results in lower energy and protein per ton, the increase in yield is usually enough to offset the decline in quality. That is, more protein and energy will be harvested on a per acre basis.

Under typical growing conditions, wheat silage yields will be in the range of 5 to 7 tons per acre of 35 percent DM forage when harvested in the late boot stage, and 8 to 10 tons per acre in the late-dough stage. Of course, drought-stressed wheat will likely produce less tonnage per acre; depending on the severity of drought, a 25-50% reduction in biomass can be expected.

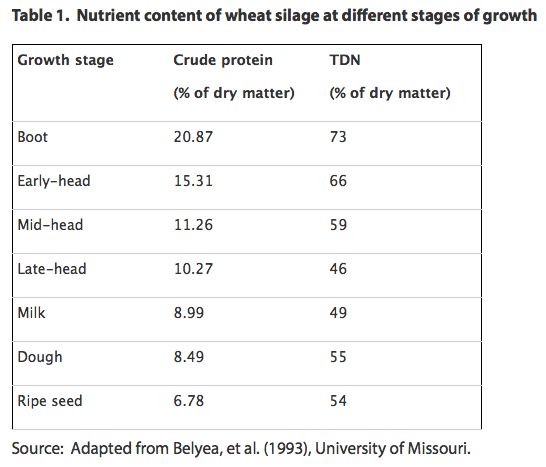

Regarding feed values, Table 1 shows nutrient content of wheat silage at different stages of growth, according to research at the University of Missouri:

Pricing Wheat Silage

One challenge for buyers and sellers of wheat silage is how to determine a sale price for a commodity that isn’t commonly traded and for which no widely accepted market price exists. Two approaches will be considered here: the first method will be to derive a silage price using feed value comparisons to a feedstuff for which more reliable price information exists. A good candidate for a proxy feedstuff in Kansas is alfalfa hay, with prices reported weekly across the entire state and for a range of quality levels. A second pricing perspective considered here is to estimate how high the wheat forage must be priced in order to provide a higher payoff than harvesting the wheat as grain.

Alfalfa hay rated as “good” quality will have 58-60 percent TDN and 18-20 percent crude protein. According to USDA Ag Marketing Service reports, “fair/good” grinding alfalfa in southwest Kansas is currently selling for around $140-150 / ton, as a reference point. Using the silage feed values for the “early-head” stage of maturity from Table 1, we see that on a dry matter basis, energy content (TDN) of wheat silage will be equivalent to or even better than alfalfa hay. The crude protein content in wheat silage, however, is slightly lower than good alfalfa.

Using the value of energy in alfalfa hay, a wheat silage price based solely on energy would figure out to about $63 per ton as fed ($180/ton dry matter basis), assuming the silage is 35 percent dry matter. A similar calculation based solely on protein content would suggest a wheat silage price of about $45/ton as fed (about $120/ton dry matter basis). These results, based on rather simplistic calculations, might be viewed as upper and lower bounds on wheat silage prices, from a feed value perspective.

A second pricing approach is to estimate a price per ton of silage which would offer a comparable or better return to the wheat grower than harvesting the wheat as grain. Net returns to grain harvest are equal to the expected yield multiplied by market price, minus the cost of grain harvest. As an example, assume a yield of 25 bu/acre with a market price of $4.80/bu, and harvest costs (based on custom rates) of $29 per acre. These values indicate a net return to harvesting grain of about $91 per acre.

Returns to harvesting wheat as silage are calculated as a silage yield of 3.86 tons per acre (35% dry matter; this is equivalent to a 1.5 ton hay yield, assuming 90% dry matter), multiplied by the $45/ton lower bound price from above, less harvesting costs of $34.74 per acre (calculated at $9/ton for chopping and hauling). This gives a net return of about $139 per acre, a more attractive option than the return to grain harvest calculated above.

Making Wheat Hay

A forage alternative that will appeal to many Kansas wheat growers is wheat hay. As mentioned earlier, wheat hay makes a very good feedstuff for a variety of cattle enterprises, and in some cases hay can be hauled farther and more easily than silage. Again, precautions are needed if the wheat variety has awns.

Past research from K-State indicates that wheat hay harvested at the boot stage would have the highest quality and less concern about awns, but that haying at the early milk stage offers the best compromise between high dry matter yield and forage quality. An earlier harvest favors higher protein content, but dry matter yields are typically 20 to 40 percent higher per acre at the later maturity. The other concern often mentioned with wheat hay is the presence of rough awns in more mature forage, which can prove irritating to cattle’s eyes and mouth. Ensiling or grinding the hay can alleviate the concern about awns.

Wheat cut for hay in the late-boot stage will benefit from the use of a crimper to speed the drying, but use of a crimper at a later stage could increase shattering losses, and the more mature crop is already at a lower level of moisture anyway. Past studies from K-State have shown that wheat hay harvested at the dough stage would have 56-62 percent TDN and 8-10 percent crude protein, on a dry matter basis.

In the case of drought-stressed wheat, drought should not have such an important impact on nutritional quality. Maturity stage at harvest will still have the greatest effect on forage quality. Wheat is a nitrate accumulator and thus testing is recommended for wheat harvested for forage. Ensiling can greatly reduce nitrate levels (30-70% reduction), thus if wheat contains nitrate levels in excess of 4500 parts per million (ppm) nitrate ensiling should be considered. Producers should consider testing wheat hay for nitrate prior to feeding if nitrate was not evaluated prior to harvest.

Pricing Wheat Hay

Coming up with a price for wheat hay can face the same challenge as that seen for wheat silage: we don’t have a widely operating market with commonly known prices. This section will use the same methods used for silage above: (i) estimate a wheat hay price calculated by comparing feed values with other forages; and (ii) estimate a wheat hay price which will offer a comparable return to harvesting wheat for grain. Note that hay prices are usually quoted for harvested forage ready at the edge of the field, so harvesting costs are included in this price. Hauling costs would typically be considered the responsibility of the buyer.

Wheat hay has almost as high an energy content as alfalfa hay, but significantly lower protein. Wheat hay priced solely on energy, relative to alfalfa, would figure out to about $140/ton as fed. However, a similar calculation based solely on protein content would suggest a wheat hay price of only about $69/ton as fed. While these values could be viewed as upper and lower bounds, they present a rather wide range and are not very satisfying guides for pricing decisions.

Given this wide range, this same approach based on relative feeding values is also estimated with a comparison to forage sorghum hay. Market prices aren’t quoted for this forage for many regions in the state as alfalfa hay, at least in the USDA-Ag Marketing Service weekly reports. However, forage sorghum hay is closer in nutrient content to wheat hay, which may provide a more meaningful range of price estimates. Using a TDN value of 57% and a crude protein value of 8% for forage sorghum hay, along with an edge-of-the-field price of $90/ton, we get suggested wheat hay prices in the range of $90 to $100 per ton.

The second approach, “what hay price does it take to beat grain harvest”, also provides a helpful reference point in this case. On the grain side, net returns to grain harvest use the same values mentioned earlier, resulting in a return of about $91 per acre.

Returns to wheat hay are calculated as a hay yield of 1.5 tons per acre (90% dry matter), times (initially) the lower bound price of $69/ton, less swathing and baling costs of $45.50 per acre (uses $12/bale for 1200-lb. bales). These values suggest a net return to hay of only about $57 per acre, much less than the return to grain. However, using a wheat hay price of $95 per ton provides a net return of about $97 per acre for harvesting hay, a slight advantage over grain harvest.

Ultimately, of course, market prices are determined by buyers and sellers. However, the discussion above provides a couple of perspectives on how interested parties might approach the problem.

Post a comment

Report Abusive Comment