By Emmanuel Byamukama, Bob Fanning and Christopher Graham

Reports of poor winter wheat plant stands have been numerous this spring. Poor plant stands have been attributed to low soil moisture and winterkill due to lack of snow cover and bitterly cold winter temperatures. However, some of the fields that have had samples tested for pathogens also had root rot problems.

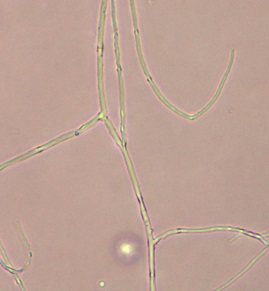

Above: Figure 1. Wheat plants killed by root rot (arrows) and not winter injury. There was good insulation provided by the residue. Photo by: Emmanuel Byamukama  Above: Figure 2. Mycelia of Rhizoctonia solani. This pathogen has mycelia that branch at 90 degree angles. Photo by: Emmanuel Byamukama |

Some root rot pathogens can reduce winter wheat survival. Samples from a few fields with dead plants were positive for Rhizoctonia root rot (Figures 1 and 2). One way to tell if the dead wheat plants are a result of winterkill or from root rot is to gently dig the plant and examine the roots. For winterkilled plants, the roots should appear normal and not rotted (Figure 3). Plants that are killed by root rot should have rotted root surfaces and sometimes will have clipped roots.

Above: Figure 3. Dead wheat plants with healthy roots. This is an example of winter kill Photo by: Ruth Beck |

The Rhizoctonia pathogen survives in crop residues and can infect wheat and other crops at any time in the growing season. Most damage will occur if plants are infected when they are young, leading to reduced tillering and stunted growth. Severe disease development as a result of the Rhizoctonia infection leads to the development of “bare patch” where portions of the field have had all plants killed or have a few plants that have survived.

It's important to diagnose the cause of dead plants this spring so that next season appropriate disease management decisions can be made. One of the risk factors for Rhizoctonia development is when weeds are killed a few days before planting. The dying roots of recently killed plants (especially when killed with glyphosate) provide a reservoir for the Rhizoctonia to develop. To avoid this phenomenon, weeds and volunteer wheat should be killed at least two weeks before planting. Because Rhizoctonia can infect many crops, rotation may not be effective in reducing inoculum, but may help control other pathogens. Fungicide seed treatments with products containing triazole, thiramor fludioxonil are effective in reducing the disease impact.

Post a comment

Report Abusive Comment