Last month, I discussed why we are seeing increased demand for crop sulfur fertilization.

The four main reasons are 1) higher crop yields; 2) depleted soil organic matter; 3) lower amounts in atmospheric deposition; 4) less sulfur contained as impurities within modern fertilizers and crop protection products.

The increased demand for sulfur is undeniable. This demand has stimulated numerous new products, new marketing campaigns and new “expertise” on how to address crop sulfur fertilization programs.

MFA’s sulfur message has been consistent for many years. Our soil test recommendations for sulfur are aggressive and based upon a combination of targeted crop yield, soil organic matter and soil texture.

We know that sulfur pathways through the soil/plant/air/water environment are extremely dynamic. I often compare sulfur’s dynamics to those associated with nitrogen.

In fact, since both nutrients are basic building blocks of amino acids and proteins, they are closely related in terms of biological pathways and fertilization requirements.

In general, the nitrogen-to-sulfur ratio in soils, plants, animals and organic residues is relatively constant at approximately 10:1. A rule of thumb concerning sulfur fertilization is to apply one pound of sulfur for every 10 pounds of nitrogen. How many crop producers in our region adhere to this ratio rule?

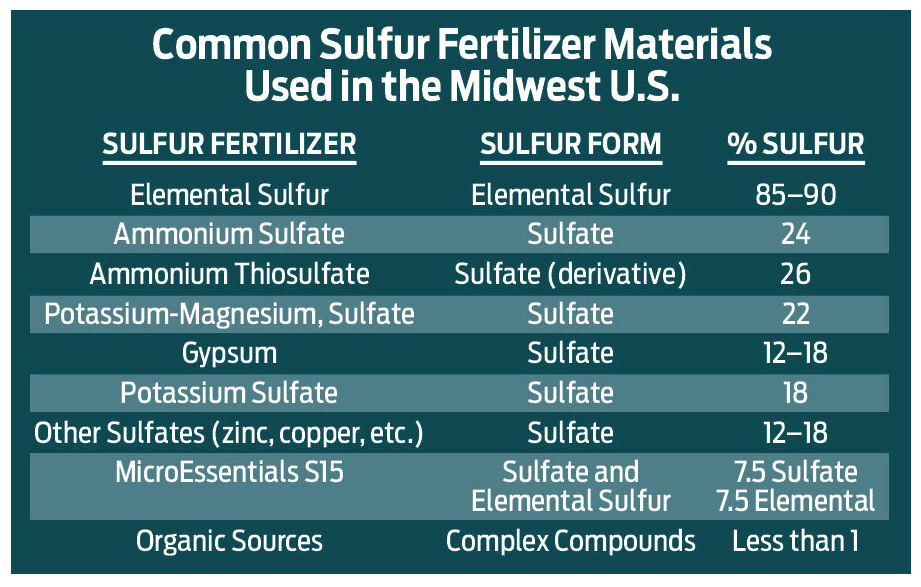

Sulfur fertilizers generally come in two major chemical forms, sulfate (or sulfate derivatives) and elemental sulfur. Organic waste products can also contain a fair amount of sulfur, but their consistency, analysis and nutrient availability is extremely variable. The nearby table lists the major sulfur fertilizer compounds used in our region.

Plant roots can only adsorb sulfur when it occurs in the sulfate form. This leads to a dilemma when choosing the appropriate fertilizer material.

Elemental and organic sources of sulfur must go through microbial-driven processes that convert them into sulfate. This conversion is moisture, time and temperature dependent, and can take from a few weeks to several months.

Sulfate-containing materials provide an immediate plant available form. However, since sulfate is water soluble and soil mobile, it can leach below the root zone with rainfall and irrigation events, and thus become unavailable to the growing crop.

We recommend sulfate-containing materials be applied near planting, as starter fertilizers or even post-emergent. These timings give us the best opportunity for crop uptake before leaching losses can occur.

The time delay for elemental sulfur to convert to plant available sulfate makes it an optimal product for fall or winter applications in front of a summer crop like corn or soybeans. It works extremely well when applied off-season with phosphorus and potassium fertilizers. If elemental sulfur must be applied near planting, a slightly higher rate is recommended.

Conversely, when sulfur response needs are immediate (at spring green-up for fescue and wheat, near planting, as a planting starter or post emergent with corn, soybeans or alfalfa), then the sulfate sulfur form is preferred.

Most sulfur products that contain micronutrients are applied in rates sufficient to satisfy crop micronutrient needs. Since these rates generally account for an extremely small amount of the crop sulfur needs and are relatively expensive.

An example of a new type of sulfur product that attempts to eliminate timing as a major factor is the MicroEssential line from The Mosaic Company. These materials contain half the sulfur as elemental, and half the sulfur as sulfate. They also conveniently place sulfur within phosphorus fertilizer granules to help obtain a more unified material spread pattern.

I expect that we’ll see many more attempts to create sulfur products that reduce the timing risk of the current materials used. As these products enter the market, please evaluate them for consistency, efficiency and compatibility.

Post a comment

Report Abusive Comment