We all know what happens with too many cooks in the kitchen and no recipe to follow. This is also the case for a farming operation with multiple owners and no formal plan for governance or decision making.

Lance Woodbury, agriculture business consultant with Ag Progress in Garden City, Kan., has been working on one such case. The land is in its fourth generation of family ownership and the owners need to begin making decisions for how to govern the land in the future.

While all seven family members own the land, only two still work it. The other five owners are spread across the country. They don’t all have the same interest in the farming operation, and currently there is minimal cash return to the owners, as profits are reinvested for growth and paying down debt.

All owners meet rarely at family gatherings to discuss a lack of group decision making. This process was simpler in generations past when all owners were farming the shared land. But separation from the land — and each other — has since made communication and decision making more challenging.

“When a family’s wealth is tied up in an asset that’s owned both by folks working in the business and folks outside the business, you want to guarantee some long-term security for the operating business and control without alienating the rest of the family who are off the farm,” Woodbury says.

“This very same problem affects almost every multi-sibling farming operation in which one or more siblings chose not to come back to the farm,” he says. “It’s a question of what do we do with this land.”

Operation at a Glance

Location: Kansas

Land: 10,000 acres

Crops: 33% corn, 33% alfalfa, 20% triticale

Livestock: 900 cow-calf pairs

Ownership: 7 family members, with 2 on-farm and 5 off-farm

Average Annual Revenue: $5,000,000

This is a challenge of putting plans in place before actual problems arise.

Case Study Scenario

The family group owns 10,000 acres in Kansas and the family members working on the farm have separate operating companies with different areas of interest.

One family member works with livestock, alfalfa and triticale, while the other focuses mainly on row crops, including corn, wheat and sorghum. Many of the crops produced go to dairies and feed yards and Woodbury says the market is good for these crops in the nearby area.

When the land was still under the third generation owners, family members all worked on the land. Now, as fourth generation owners have begun to take ownership fewer family members farm full time.

As more people join the group of owners, Woodbury says they have to decide if they’re going to split the land between each owner or if they’re going to put the land into a business entity.

“If the land is passed individually to owners and split up among them, then any owner who comes back to the farm will have to negotiate individually with each of the other landowners in order to rent or lease the land they want to farm. The individual landowners could then potentially decide to rent their cut of the land to a non-family member,” he says.

To avoid this, the family has already set the land up within a business entity, so the owners are each shareholders. In this way, when the two on-farm shareholders want to negotiate renting the land, they don’t have to work with separate shareholders for each acre of land they rent. They rent the land and negotiate rents through the business.

When working with ownership groups that are trying to form a land entity, Woodbury says it is important to explore the tax issues associated with different types of entities. C-Corporations, S-Corporations and Limited Liability entities all have different legal and tax considerations.

Woodbury explains that putting the land into an entity can discourage family members from selling assets because of the tax issues and the negotiations involved in an exit.

Now that the land is set up as a business entity, Woodbury says the family needs to develop a system of communication among the owners to allow it to function like a business.

“The goal is to treat this as a typical non-family landowner, with documents and formal leases in place,” he says. “That way, if you were an outside family member looking into the relationship, you would see there’s a fair market lease between owners and they’re not transferring family wealth through a low rental rate.”

Managing Expectations

Woodbury says it’s often less difficult to control and make decisions for the future of land and farming operations when everyone is involved in the daily operations.

“When the people who buy all the land are also the ones farming, there’s less potential for conflict,” he says. “We bought the land, and we can pay ourselves rent, and to some extent manage some tax issues, and decide how we want to do things in the future.

“Any solutions going forward hinge on deciding who will make decisions for the land entity…”

“The beauty of this case is we’re just at the front end of this particular challenge of how to govern the land company with off-farm heirs, so it’s about managing expectations and defining what their future guidelines will be,” he says.

Woodbury has recently begun working with the family on the beginning stages of strategizing a solution to their operations and control challenges. It hasn’t hit a critical point yet and there are currently no problems with any of the owners wanting to leave, expand or add more owners. But it’s essential, Woodbury says, to manage the expectations of all the owners and devise a plan and system for how to make decisions.

One on-farm owner first approached Woodbury with this concern.

“The on-farm owners look at this situation and think, ‘If we play this out 10 years, there are two of us and five of them and we’re going to be answering to them. How do we make sure we have good relationships and they feel good about their investment so we have security in our farming operations?’ Right now we’re setting the groundwork for this generation and maybe even the next two or three generations.”

If a few owners were to decide they aren’t getting enough out of ownership and decide to leave, the other owners could be left trying to buy out the other family members, which might require selling assets to generate cash, reducing the size of the operation.

If they don’t get on the same page about running the operation, they could wind up in court, as other families have.

“I saw an example of this a few years ago,” Woodbury says. “There were some off-farm owners and a few on-farm owners who controlled the land and made all the decisions. The on-farm owners never passed any money out to the off-farm owners and just kept reinvesting in land. The off-farm owners took their brothers to court.

“By the time they paid all of the attorneys and accountants involved, the cost of that conflict going through the judicial system forced the sale of land. So the financial consequences of a fight, because they weren’t on the same page, are severe,” he says.

Meet the Expert

Lance Woodbury

Ag Progress

Garden City, Kan.

913-647-4064

lance@agprogress.com

Lance Woodbury is a mediator and facilitator at the agriculture business consulting firm, Ag Progress, located in Garden City, Kan. Since 1995, Woodbury has been focusing his consulting efforts on closely-held agriculture businesses and professional services firms.

He spent 14 years at Kennedy and Coe (now K-Coe Isom), a top 100 accounting firm, in a number of leadership and consulting roles. He also has served as the Economic Development Director of Wichita County, Kan., and worked at a cattle feed yard in Leoti, Kan.

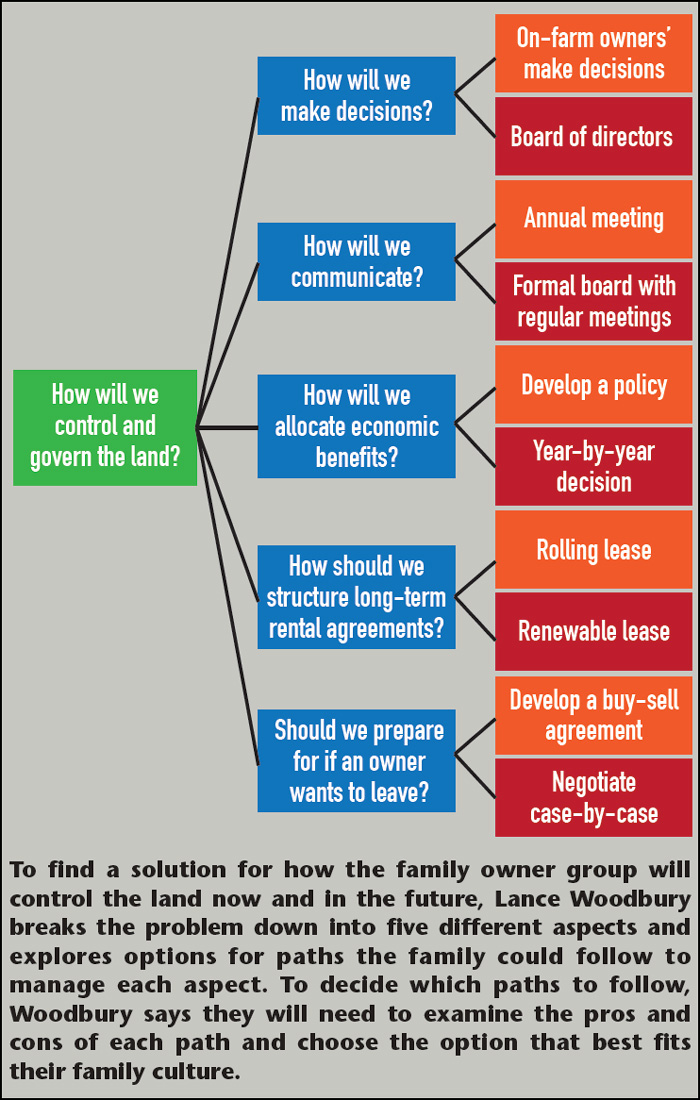

There are several factors Woodbury says the owners need to consider to create a system to manage and control the farm operation to everyone’s satisfaction and keep all of the owners on the same page. They need to decide how they will determine decision rights, and communicate how to allocate the economic benefits and profits of the land, how to handle long-term rental agreements, and how to deal with owners no longer interested in ownership.

“At some point, the family will need to have a series of meetings about how they’re going to make decisions about the entity and they’re going to have to spell out that decision-making relationship,” he says. “They’re going to need to create some policies that govern the future actions and decisions.”

Professional Consultant’s View

Any solutions going forward hinge on deciding who will make decisions for the land entity, Woodbury says.

“Are the two on-farm owners going to control the land entity, or is that a conflict of interest because they will then be renting land to themselves? If not, will there be a board or must all of the owners reach a consensus and be in unanimous agreement?” he asks.

The owners need a system of making decisions about a slew of issues and topics that can arise. Will they reinvest all profits in the land? Or will they distribute money to the shareholders? Will they expand the operation? How will they manage rental agreements? What if another owner wants to come home and begin farming the land?

To address this, Woodbury suggests two possible solutions the family could take.

First, the family could provide control to those on the farm through different classes of stock or partnership units and decision parameters covered in legal documents.

For purposes of illustration, shareholders could be given voting and non-voting stock. Those with voting stock would make decisions for the land entity and those with non-voting stock would take a more passive role with limited decision-making power.

If the family gives the voting stock to the on-farm owners, it would keep control of the asset with those who depend on it for their livelihood. Decision-making rights would then be with those who have the best understanding of how to care for the land. But it could also create a conflict of interest for the on-farm owners.

“If you leave control with the people on the farm, there is a natural conflict of interest because they not only control the land, but they’re also leasing the land to themselves,” Woodbury says. “It can become a situation where, because they’re in control of the land, they don’t need the other owners’ input as they’re leasing the land to themselves.”

This mentality can eventually drive the non-voting owners to sell their shares, which again leaves a few family members with the financial burden of trying to buy their family members’ shares.

For this reason, Woodbury says this solution is not preferred by most.

A better solution might be to use a board structure for decision making and provide long-term rolling leases to the on-farm owners.

This solution gives all of the owners more control while still providing security for the on-farm owners. It will require good governance practices and evaluation systems to make sure the broader group is knowledgeable about the farm operations and the land entity. This is the option recommended to the family.

“This solution makes each owner feel like they have more of a voice and a say in what happens to the land,” he says. “They feel like they have some influence over what happens with their share.”

The question then becomes what happens if one shareholder decides to sell their share. This is another aspect the family will need to cover when making decisions about the future of the land entity. Will they have a buy-sell agreement or just deal with these cases on an individual basis?

Developing Communication Systems

When there isn’t an agreed-upon system for communication, Woodbury says families can tend to make too many assumptions about the desires and aspirations of other family members.

“Some questions don’t get asked that you might ask in a non-family business. Then things never get talked about,” he says. “I see family businesses where they only touch base at family gatherings, and it doesn’t lead to the kind of focused planning and thinking you would get if it wasn’t a family business.”

Woodbury says an annual meeting with periodic phone or email updates from those on the farm about crop and land conditions could help bring order to the communication process. This system isn’t time intensive and is driven by those on the farm and closest to the land.

It’s efficient from a communication perspective, but may not provide enough involvement for those who are emotionally attached to the land and are dependent on just two owners to drive the communication.

Woodbury advises more shared responsibility in the communication system that fully utilizes the broad skillset of all of the owners, instead of just the two on-farm owners.

This arrangement provides a formal governance mechanism that can last for generations and allows for different members to be involved and to utilize their expertise. However, Woodbury says it can be difficult to find time for meetings when many of the family board members are focused on their other jobs and building their careers. The formality of meeting and voting can also be awkward for a family.

To choose between annual meetings and a formal board, Woodbury says it’s important to poll every owner and see what level of involvement they want. He stresses, again, not to make assumptions about what a family member wants. If there is a split and some owners want to be involved regularly while others only want to be updated once in a while, a hybrid of the two possible solutions could be made.

“They could have a board meeting once a year, but maybe have monthly communication from the people on the ground about what’s going on and those who have interest and knowledge of the land could meet a little more frequently,” he suggests.

“The family has choices and can tailor a solution to their culture and situation. They might not choose the best or preferred option from my perspective, but that option won’t necessarily always fit their culture. It’s more important that they use a system they can stick to that works for them.”

Allocating Profits

“Land, historically, has produced low cash return. It appreciates in value, but for passive landowners, the cash return is not very high,” Woodbury says. “The owners who live off-farm have this land on their balance sheet, but it might not be producing much income.”

This brings up the issue of how the land entity’s profits will be distributed. The family needs to decide if the profits will be distributed to each shareholder or reinvested into the land. Either way, Woodbury says there needs to be a plan in place.

The family could develop a policy regarding the distribution of profits and reinvestment for growth, which would allow for planning for the future and create consistent expectations for cashflow.

This solution could come under pressure, though, as shareholder needs and wants change. There could be large amounts of cash that some shareholders feel would be better used if distributed to the group. There could also be decisions about how the reinvested dollars will be spent that could be contentious.

For this solution to work, the family would need to decide what the expectations for return are and develop an investment policy for the reinvested money, Woodbury says.

Another option would be to determine on a year-by-year basis how profits are distributed. This way, the distribution or reinvestment of money could be decided yearly and adjusted to market opportunities and shareholder needs.

Opening the question of how to allocate funds each year, though, makes it difficult to reach a consensus and could hurt long-term planning because a reinvestment strategy might be short-lived.

“If they have an agreed upon policy, then they only have to have a conversation when someone wants to change it,” Woodbury says. “If you choose to bring it into discussion and decide every year, that can be cumbersome. It can be painful. It makes it very difficult for the family members working on the farm and for those involved in decision making because they don’t know if they are going to get the money to make improvements and reinvest or if the other owners are going to want a payout.

“That said, I lean toward creating a set policy and going back to change it only when an issue arises,” he says.

Creating Long-Term Rental Agreements

Woodbury says it’s important that the on-farm owners have fair, market-based terms for their leases and rental agreements from the land entity. He adds that it’s equally important that the family members have some security in their rental agreements.

“The family needs to make sure there are good leases in place between the land entity and each of the on-farm owners. You want to be able to look at the agreement and see that there’s a fair market lease between the family member and the land entity and they’re not transferring family wealth through a low rental price,” he says. “We want to treat this as if it was a non-family landowner. We need to get things documented and have formal leases in place.”

Rolling vs. Renewable Leases

There are two types of leases that Woodbury says would work in this family’s situation: either a rolling lease or a renewable lease.

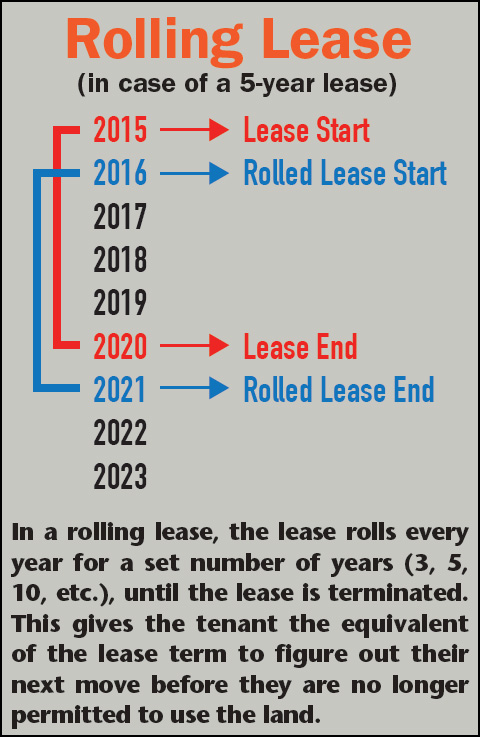

A rolling lease is a rental agreement in which the lease will renew every year for “X” number of years until the lease is terminated, giving the on-farm owners X number of years after the lease is terminated until they will no longer be able to use the land.

For example, if it’s a 5-year rolling lease beginning in 2015, the lease end date would be 2020. The lease will automatically renew, or roll, in 2016 for another 5 years unless the lease is terminated. So, no matter when the lease is terminated, the on-farm owner still has 5 years of advanced notice that they can no longer use the land.

This creates a sense of certainty and security for the on-farm owners because they will have a planning window should the lease be terminated. The longer notice also encourages the on-farm owners to do more land improvements, as they will be more likely to see the fruits of their labor.

On the downside, Woodbury says rolling leases don’t allow quick changes should the off-farm owners be unhappy with the on-farm owners’ performance. Without flexibility or regular review of a lease, it could also put the lease above or below market value at certain times, he says.

“Rolling leases could seem stacked in the on-farm owners’ favor, but when you think about the fact that they will be buying combines and farm equipment with a heavy capital investment, they need some certainty in their operational business model,” he says.

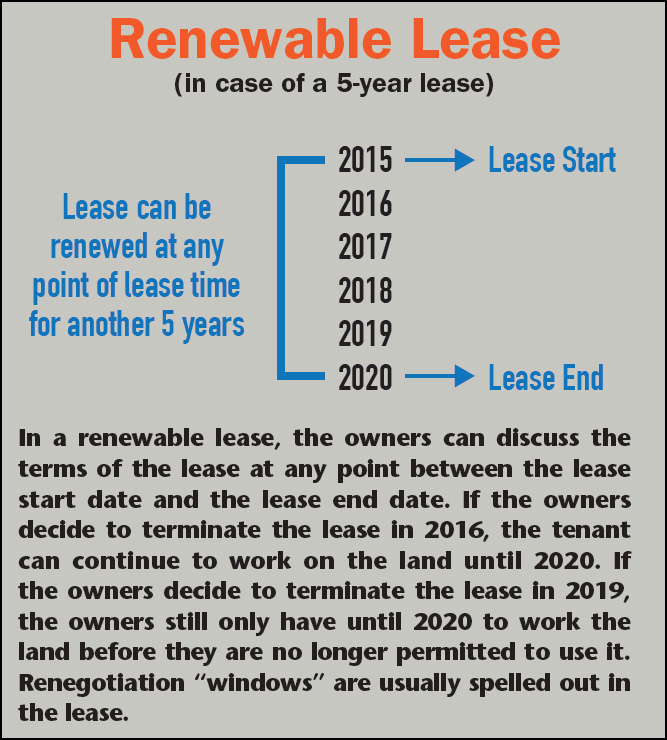

A renewable lease is one in which terms for the lease’s renewal are discussed during the lease period. The lease time frame stays fixed until the lease is renewed. For example, if it is a 5-year renewable lease beginning in 2015, the lease will end in 2020 unless it is renewed at some point between 2015 and 2020. Many leases will specify, before the end of the lease, when renegotiations should occur. If renegotiations occur in 2018 but fail, the farmer has at least two more years to make changes to his business. But if the negotiations are successful the renewal might include an additional three years, which effectively puts the end of the lease in 2023.

“With a renewable lease, you could still have a 5-year lease, but at year 3, 4 or 5 the family will need to sit down again,” Woodbury says. “The real difference with a rolling lease is that you get a longer window of time for the person operating on the ground to make decisions. A renewable lease may have a shorter window and provide for a more intentional discussion and evaluation by the landowner and the tenant.”

Woodbury says the benefits of a renewable lease are that it offers some long-term security, but perhaps not as much as with a rolling lease. It also encourages the off-farm owners to be more involved in reviewing and improving the renewal terms through research and evaluation.

However, he says renewable leases can create a lot of stress and uncertainty around renewal times that could damage the business relationship if the family’s personal relationships aren’t strong.

So which option is better? Woodbury says it’s all about how involved the off-farm owners want to be.

“If the family isn’t very attached to the land, a rolling lease might be preferable in terms of giving the maximum amount of security to the on-farm owners,” he says. “But my preference in this situation would be the renewable lease because it forces the owners to get to the table every so often and talk about it. With the cyclical nature of this industry and commodity prices currently coming down, for example, if you’re locked into a rolling lease, you’d want to have some detailed provisions to spell out how to renegotiate the lease if crop prices fall.

“If crop prices fall and the on-farm owner or tenant is locked into the lease and it’s too high, it could create a headache in terms of trying to renegotiate things. If you’re in a renewable lease, every 2 or 3 years you know you’re going to be back in the room discussing the terms and you can adjust and make up for fluctuations in the value of the land,” he says.

Focusing on the Future

As time passes, decisions on how to add or remove owners and shareholders from the land entity will arise.

“If someone wants out, we may want to have a formula by which they can exit. But not all families are eager to do that,” he says. “Some families say they don’t even want people to be thinking about getting out, so they’ll wait until something happens and have a fight. I prefer they figure it out before the problem arises so there’s some certainty around how things will happen.”

If the family creates a buy/sell agreement, Woodbury says it would help them understand the terms for a future exit. However, all owners need to agree on what is fair. If some shareholders are unhappy with the agreement, they could stay in even though they don’t want to and make decision making difficult. Or, worse, Woodbury says they could challenge the buy/sell agreement through legal action, which could cost the family.

Another option is to allow for exits to be negotiated independently as they arise. This solution considers the needs and negotiating ability of each shareholder. Woodbury says this system often encourages owners to stay in unless they are willing to spend a lot of time and energy negotiating to get out.

“I’ve seen other families use this method and the result is that all of the owners stay in because nobody wants to be the first to get out and lead the way,” he says.

This solution can create potential hardship for the family and the land entity if the process turns into a fight and goes to court. There can be significant difficulty if several owners decide to exit at once, which could force the remaining owners to sell significant portions of the land in order to buy out the others.

3 Homework Questions

LanceWoodbury, mediator and facilitator at the agriculture business consulting firm, Ag Progress, says if he was a part of a farming operation with multiple owners, three of the most important questions he would pose include these:

1. What is most important to your family – keeping assets together, creating flexibility for family members, or generating cash for shareholders? What do you believe are the elements of a “successful family business?”

2. Do your family members have the trust and respect of one another to handle a long-term business relationship?

3. What expectations do you have of business partners and other owners?

Click here for the expert’s responses to these three questions.

Woodbury’s preferred option of the two is for the family to figure out a policy so there is some certainty about how the family would afford to buy out an owner.

Keep the Discussions Going

“Keeping the communication alive is really the most important part for this family as they’re just at the beginning of figuring these things out,” Woodbury says. “They need to stay in the process and keep implementing it little by little and reevaluating what’s working for them, and maybe what isn’t.

“They need to be asking themselves, ‘Is this what we want? Do we feel good about our decisions? What else do we need to do? What other provisions need to be put in place? What things can strengthen this?’ These are important questions to ask throughout the process of picking and sticking to a solution.

“Getting the communication started before a succession event is critical, and this family is doing that now, so they are on the right track,” Woodbury says. “But what can happen is they don’t have the conversations and someone dies or tries to sell and they’re stuck sorting everything out in the middle of a family transition. It’s that much harder to make these long-term governance decisions when you’re in the middle of a stressful situation. It’s vital to communicate and make decisions for the future before there’s a trigger or an event that forces these types of difficult conversations.”

As for what decisions this family will make, Woodbury says it’s still too early to tell, but he does have hope for where he’d like to see them go.

“My hope would be that they choose to have everyone involved in the governance of this land entity in the form of a long-term, formal board of directors, not just the two on-farm owners making decisions for everyone,” he says. “Having a board is a more sustainable system for governance and having the land set up in an entity suggests that they’re going to be around a long time.”

As Woodbury said previously, all of the family’s other decisions will hinge on them choosing a system for decision making so they can decide on what other measures to put in place and what those measures should look like.

Web Exclusive: Expert Responses

Click below to view other case studies from this report:

Post a comment

Report Abusive Comment