There has been a great deal of interest in recent months in the idea of using nitrogen fertilizer during the growing season to increase soybean yields. This is somewhat surprising given that there has been so little evidence from published and unpublished reports showing that this practice increases yields, let alone provides a return on the cost of doing this.

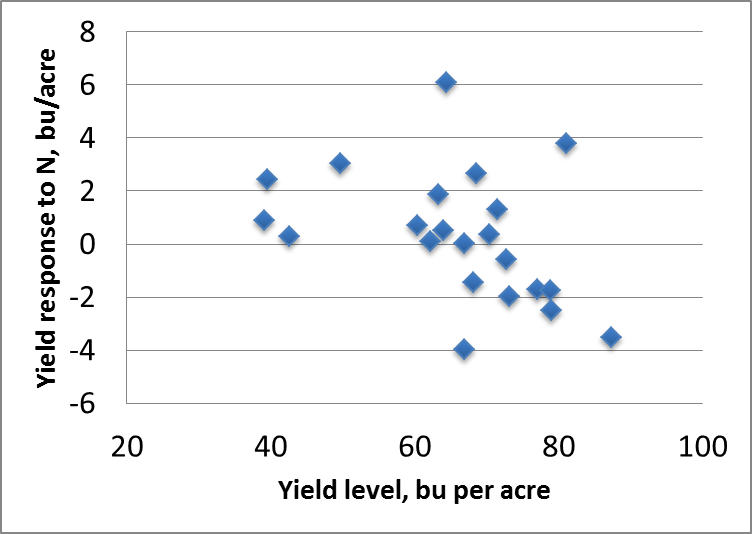

Figure 1. Response of soybean to N fertilizer in 22 Illinois trials, 2010-2013. |

Soybean plants in virtually every Illinois field produce nodules when roots are infected by Bradyrhizobium bacteria, and bacteria growing inside these nodules are fed by sugars coming from the plant. In one of the more amazing feats in nature, these bacteria are able to break the very strong chemical bond between N atoms in atmospheric N2 (N2 makes up some 78% of the air, but is inert in that form.) This “fixed” N is available to the plant to support growth.

The soybean crop has a high requirement for N; the crop takes up nearly 5 pounds of N per bushel, and about 75% of that is removed in the harvested crop. It is generally estimated that, in soils such as those in Illinois, N fixation provides 50% to 60% of the N needed by the soybean crop. A small amount of N comes from atmospheric deposition, including some fixed by lightning. The rest comes from the soil, either from that left over from fertilizing the previous corn crop or from soil organic matter mineralization carried out by soil microbes.

Nitrogen fixation takes a considerable amount of energy in the form of sugars produced by photosynthesis in the crop. Estimates of the amount of energy this takes range widely, but could be in the vicinity of 10% of the energy captured in photosynthesis, at least during part of the season. Because photosynthesis also powers growth and yield, it seems logical that, especially at high yield levels, the crop might not be able to produce enough sugars to go around, and that either yields will suffer or N fixation will be reduced. Would adding fertilizer N fix this problem, resulting in higher yields?

We’ve added fertilizer N in a series of trials over the past several years, with some of the research funded by the Illinois Soybean Association. These studies involve application of urea, in some cases with Agrotain (urease inhibitor) or as ESN (slow-release N) during mid-season, usually in July. Figure 1 shows the result of 22 such comparisons between 2010 and 2013.

Yields ranged widely among these studies, but in only one case did adding N fertilizer significantly increase yield (by 6 bushels per acre) and there was no relationship between yield level and response to fertilizer N. With yields as high as 80 bushels per acre, these results provide no support for the idea that the higher the yield, the more response to fertilizer N. In fact, yields above 70 seemed more likely to show yield decreases from adding N, though these differences were small and not statistically significant.

While these results don’t prove that adding N fertilizer doesn’t increase soybean yields, it clearly shows that we can’t count on such an increase, and it certainly calls into question the wisdom of making such applications, at least with our current state of understanding. It is possible that soils often contain more N than we realize, especially under good mineralization conditions, which are also good growing conditions. It is also possible that we don’t really understand the photosynthetic capacity of soybeans under field conditions, and that our guess that yield is limited by photosynthetic rates when the plant is also fixing its own N is just incorrect.

The usual signal of N deficiency in crops — light-green leaves — is rarely seen in soybean plants during the period of pod-setting and seed-filling, unless the crop is under prolonged drought stress. Late in seed-filling, leaves start to mobilize their N as chlorophyll and photosynthetic proteins break down, and much of this N moves to pods and into seeds as photosynthesis winds down. If there were a way to get more N into the leaves early in this process, it might be possible to maintain photosynthesis a bit longer and move more material into seeds. It is clear that getting this to happen consistently will be difficult, especially under an unpredictable water supply.

Until and unless we find a way to learn to make N application to soybeans work consistently, or in most cases to work at all, this practice increases both economic and environmental risk. Under dry late-season conditions such as we experienced in 2013, much of the N we apply will stay in the soil, and become part of the mobile pool of soil N going into the fall.

One way to get a better look at this over a wide range of fields and soils is to put strips trials in farm fields. These can be done using aerial or ground application, but ground application is easier to track, if more difficult to do. If you have interest in running such a trial, I’ll be glad to suggest a design.

Related Stories:

Post a comment

Report Abusive Comment