By Mike Abram

It’s unusual to become farm manager without any actual land to farm. But that’s exactly the situation Oliver Scott walked into when joining Bradford Estates in February 2021.

At that point the 4,800ha estate’s farming operation was carried out entirely under various Agriculture Holding Act (AHA), Farm Business Tenancies (FBT) or contract farming arrangements.

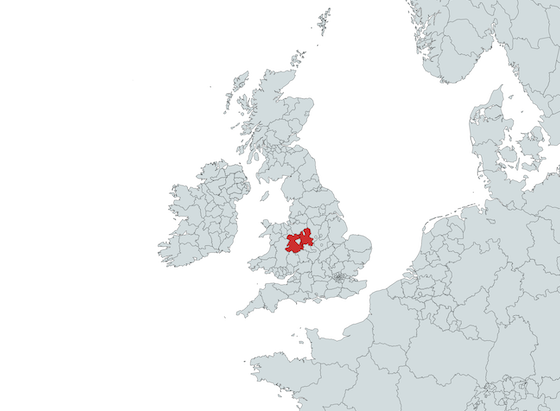

The estate, which stretches across parts of Shropshire and Staffordshire, was seeking to bring back more control under managing director Alexander Newport’s direction.

“This will help diversify the estate away from just investment property into more operating businesses, giving us more resilience and diversity,” Newport says.

That led to Scott’s appointment, and 1,600ha being taken back in hand on the estate, mostly from two different management regimes, with further land expected to be added in the future.

“I turned up with a blank piece of paper – with no team, no machinery, and no land until August,” Scott says. “So I spent the first six months getting to know the estates and writing a farm business plan about how the new farming business would look over the next five years.”

One clear direction of Scott’s was to take a more regenerative approach. The business plan aims to use 15-20% fewer inputs over the next five years, with an allowance of 5-8% decrease in yield while the system beds in.

At time of writing the business plan, that would have increased margins over a more intensive maximum yield approach, he says.

“Going from a system that is averaging 8.6 tons per hectare for winter wheat in a high-input, high-output system, reducing inputs by 20%, and then if we can average 7.5-8.0 tones per hectare, the margin would be better.

“Obviously the current commodity prices have distorted that, but they haven’t changed our view that we should become regenerative farmers.

“We can’t let the market dictate too much what we are trying to achieve. The market might be like this for the next three years, but the longevity of what we are trying to achieve is for the next 20 years.”

Taking Time

Implementing the plan is going to take time on the two contract farming operations taken back in hand, Scott.

“The two farms are like chalk and cheese,” he says.

One was geared up around high value crops, with potentially two or three root crops in a five-year rotation with some occasional chicken muck applications, plus solid and liquid digestate, while the other grew high value crops on a smaller scale, had straw for muck deals, and used more minimum cultivations.

“My brief is to look at the regenerative model, but we’re very much taking conventional farms into that system,” he says.

A starting point has been to zone the farms into distinct areas for detailed soil analysis by Sustainable Soil Management through Hutchinson’s agronomist Ed Brown. The survey will give a baseline for the condition of the soil, including chemistry, physics and biology.

One immediate benefit of the soil survey is to inform decision-making around cropping and the rotation, and how quickly he can transition to a more sustainable approach.

“It’s going to take time to get the rotation right, and for it to work as a whole farm and not two half-farms,” Scott says

Longer Rotation

The present plan is to lengthen to a nine-year rotation, which will include one year each of potatoes and lettuce, with the rest in combinable crops including cereals, spring soybeans and corn, plus grass and lucerne. Cover crops are being grown before any spring crop in the rotation, which are destroyed through some combination of grazing, topping and glyphosate.

He recognizes some might question whether a rotation with potatoes and lettuce can truly be described as regenerative with the soil movement typical for these crops. But with the soil type suitable for growing high value crops, he says it is important to work out how to do so sustainably.

“I think technology such as gene editing and more autonomous machinery will help, while I would argue with a nine-year rotation, we are regenerating our soils,” he says.

Lettuce offers some particular potential with requiring less soil movement than potatoes, and an earlier harvest in August allowing a simple catch crop of buckwheat or turnip rape to be grown ahead of drilling a wheat crop into the green in September or October.

Bradford Estates proposed nine-year rotation and preparation | |

|

Rotation |

Average yields in 2021 |

|

Winter barley |

8.6 tons per hectare |

|

Oilseed rape |

3.5 tons per hectare |

|

Winter wheat |

8.9 tons per hectare |

|

Spring beans/peas/oats |

Spring beans – 3.5 tons per hectare |

|

Winter wheat/rye |

|

|

Corn/poppies |

|

|

Winter wheat/spring barley |

Spring barley – 6.6 tons per hectare |

|

Potato/salads |

Potatoes – 54 tons per hectare |

|

Winter wheat |

|

Source: Farmers Weekly

Soil Surveys

A key indicator of success will be future soil surveys to highlight whether soil health is improving.

With no machinery on farm, he has been able to start from scratch, with flexibility a priority. That’s led to two 6-meter (20-foot) drills – a Horsch Avatar disc drill bought brand new using a grant, and a second-hand Horsch Sprinter – rather than one 12-meter (40-foot) machine.

While the Avatar provides flexibility in being able to direct drill or behind various cultivations, the Sprinter brings extra flexibility if conditions are not suitable for a disc drill, or different crops need drilling on the same day if weather has delayed drilling.

In the current cropping year, he met his target of direct drilling 25% of the cropping with the Avatar, including much of the spring cropping and cover crops, while spring beans into covers were drilled with the Sprinter with inch coulters. Over the next four years he aims to increase that to 40% direct drilled.

Livestock Integration

Another key plank of most regenerative systems is to integrate livestock. Scott is already developing plans not just to use them for grazing, but also in the longer term to potentially create a closed fertility or circular farming system producing all the farm’s fertilizer requirements.

“It’s probably going to be 10 years in the making,” Scott says.

He used a flying flock of sheep last winter to graze cover crops. The goal is eventually graze 1,400 sheep, probably split between the estate and another owner in a partnership arrangement, also involving a local shepherd to manage them on a day-to-day basis.

Scott is also considering running beef cattle outside for six months of a year, and housing them for the other six months to supply solid and liquid manures, in a system that fits between a commercial finishing unit and pasture for life all-year-round grazing.

“With fertilizer at £900 per ton, it’s got everybody thinking about how they can use muck and slurry in a better way,” he says.

He does have some concerns over how Farming Rules for Water legislation might affect his plans but is hopeful that can be navigated successfully through discussions about the system’s goals.

“We know we will need to invest in facilities to store it correctly so it is not leaching into drains or fields,” Scott says.

Related Content:

What I've Learned From No-Tilling: Putting Worldly No-Till Knowledge To Work: After years of helping countless farmers make a lot of money, Bill Crabtree finally decided to make a go of it himself. In 2007, he bought 7,000 acres of farmable ground in northeast Morawa, Australia.

Zapping Weeds, Smashing Seeds: With growing concerns about herbicide resistance, Australian no-tillers are looking at new non-chemical ways to control serious weed problems.

Helping Zambia Reach its ‘Huge’ Farming Potential: Longtime Australian no-tiller Bill Crabtree is playing a major role in an organization determined to help Africa adopt modern farming methods.

The No-Till Passport series is brought to you by Martin Industries.

Since 1991, Martin Industries has designed, manufactured and sold leading agriculture equipment across the U.S. and Canada. Known for Martin-Till planter attachments, the company has expanded to include a five-step planting system, closing wheel systems, twisted drag chains, fertilizer openers and more in their lineup. Their durable and reliable planter attachments are making it possible for more and more farmers to plant into higher levels of residue.

Post a comment

Report Abusive Comment