Newly minted Michigan State University Ph.D.’s Glover Triplett and the late Dave Van Doren arrived at Ohio State University (OSU) in the late 1950s. Within a few short years, the pair began the world’s first no-till research project at the Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Center (OARDC), Wooster, Ohio.

Like the farmers they were serving, their scientific curiosity and determination helped them ignore the critics and stay the course. Their research, before the arrival of effective no-till seeding equipment and herbicides, provided the foundational knowledge to spur the most momentous change in farming since the tractor displaced the horse.

The duo seeded its first no-till plots in Wooster (Snyder Farm) in 1962 and Hoytville (Northwest Research Station) in 1963, which remain the longest continuously maintained no-till plots on the planet. (Illinois’s Dixon Springs plots were no-tilled in 1961 but lost support in the early 1990s after agronomist George McKibben’s death.)

No-Till Requires Long-Term Study

No-till is an example of a practice that can’t be evaluated instantly, says retired OSU ag engineer and No-Till Legend Randall Reeder.

“The soil biology and soil structure in a long-term no-till field is almost totally different from one that’s been tilled every year. It’s dramatic – you can see it in tilled vs. non-tilled soils across the road from one another – but it doesn’t happen overnight. It takes continuous no-till to build up the soil.

“Jerry Grigar, the now-retired Michigan state agronomist for NRCS, discovered that a lot of papers are written based on 3 years of data, which is transitional no-till. They may or may not show a benefit to no-till, whereas if they’d kept it going for 5-10 years, the results might have been dramatically different in favor of no-till.”

Michigan State University, which recently completed 30 years of long-term no-till at its Kellogg Biological Station, reported that while yields increased every year in no-tilled vs. tilled treatments, long-term studies are essential because they reveal unexpected results. “There were many slices of time when we would have gotten the wrong answer if the study had lasted less than 10 years,” concluded MSU ecologists.

To mark 60 years of research and data on continuous no-tillage at OSU, we interviewed Triplett, Ohio farmer and former NRCS Chief Bill Richards, retired OSU ag engineer Randall Reeder, retired Chevron rep Bill Haddad and too-many-to-count email exchanges with Warren Dick (retired Emeritus Professor of Soil Science at OSU, who had primary responsibility for the plots from 1980-2016). After collecting more than 100 pages of articles, transcripts and notes, several more items are found at no-tillfarmer.com (see For More Information sidebar below).

Sod Seeding First

While pursuing his master’s degree at Mississippi State University, Triplett worked with the sod-seeding practice, which he described as “planting winter oats for winter grazing in a sod pasture.”

By the time he’d arrived at OSU, the new herbicides opened his imagination to try a similar concept for corn production. While controlling the vegetation and getting the seed corn in the ground would be challenges, atrazine was becoming available. “Why wouldn’t the practice work for corn in Ohio – if we can control the weeds?” he asked.

He wasn’t the first to try it, but his timing coincided with more tools for the practice. A couple of years earlier in 1960, Virginia Tech weed scientists had begun no-till work. “Their graduate students used a soil probe to take a plug out and put seed in those individual holes. At OSU, we had ag engineers, especially Bill Johnson, who made several modifications to a planter so it could work without no-tillage.”

‘Just Do It’

The still-new professor didn’t seek permission to put OSU into the no-till research business. But he swiftly heard skeptics’ voices. Triplett was eager to retell a story that is now no-till lore. “My late wife grew up on a farm in Mississippi and her father took pride in clean cultivation. After I’d been at this for a couple of years, I took her out to show her what I was doing. We looked at some corn plants about a foot tall in a field, where there’d been corn the previous year. The old stalks and dead weeds were there. She said, ‘Glover, this looks terrible. They’re going to fire you,’” he recalls.

“Triplett and Van Doren threatened to separate agriculture from the plow, a pairing that went together for thousands of years…”

“Critics would say ‘Yeah, you might be able to get by without tillage for 3-5 years, but sooner or later you’ll need to plow that ground.’”

They cited compaction or fertility problems that could only be fixed by stirring the soil. Triplett was intent on taking the mystery out of such statements.

Getting Started

As they started their research, Triplett and Van Doren posed 4 questions that were most provocative in 1962. “They threatened to separate agriculture from the plow, a pairing that went together for thousands of years,” says Dick.

- How much tillage, if any, is needed to grow a crop?

- How do tillage and rotation interact to influence yields of corn?

- What effect does soil type (heavy clay in northwest Ohio and lighter soils in Wooster) have when tillage is reduced?

- How to manage weed control and nutrients?

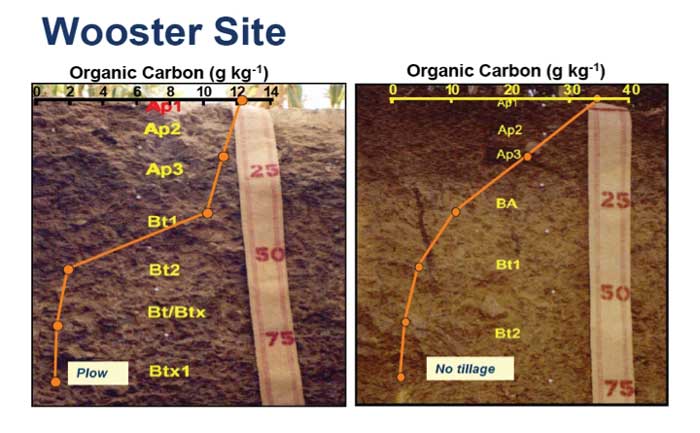

TELLING DATA. A significant difference is seen in soil organic carbon from the plowed and no-till plots at Wooster. Ohio State University

The Wooster and Hoytville plots were set up for experimental designs in tillage (no-till, chisel and moldboard plow) and rotations (continuous corn, corn-soybean and corn-oat-hay). “These tillage and rotation plots are pretty much untouched by any other factors than the normal management factors to maintain the plots,” says Dick.

First Impressions

Ohio no-tiller and No-Till Legend Bill Richards, who’d later become head of the NRCS in Washington, D.C., was intent on reducing tillage since graduating from OSU in 1954. “We tried crazy things. We made a planter and hung it on the plow. The next move was plow-plant and later that turned into stale seedbed planting.”

Richards recalls meeting “Trip” in either 1962 or 1963. “A fraternity brother had taken me to a Farm Foundation seed meeting and farm tour at Wooster. This young guy came out to tell us what he was doing. Most of those seed guys laughed at him; they thought he was crazy. I crawled off the wagon and stayed there – I thought ‘this guy speaks my language.’ That was the beginning of our friendship. We started trading ideas and I told him what I was doing with plow-plant and till-plant. I suppose his reaction was that I was still doing more tillage than I should.

“Meeting Trip changed the world for me. What we’d been trying to do took much too much power, and we were moving too much material.”

Key Discoveries

Dick says Wooster’s no-till proved beneficial from the very beginning. “But at Hoytville, which had the heavier silty clay loam soils, no-till consistently gave a yield penalty in the early years – sometimes a large one. So back then, many university extension services were saying that while no-tillage might work in lighter soils, don’t try it in heavier soils.

“But in later years, that wasn’t the case. When we continued to do no-till on heavier clay soils, it changed,” says Dick. “Hoytville eventually responded positively to no-tillage, but it took longer for the transition to occur.”

For Triplett, erosion control was the key discovery, and he saw the impact not just at OSU but also at the USDA plots at Coshocton, Ohio’s hilly terrain, where he’d planted in no-till. “They had a means of measuring the soil that was coming off at the bottom of the plots, and instead of tons per acre, it was pounds per acre. That decrease in soil erosion by 50 times or so was saving our soil. Some long-term tillage plots eroded to the point that they had to put more soil back on. With the no-till, you can’t see any major erosion.”

Richards cited two important discoveries. First was the importance of residue on the surface. “We couldn’t go halfway. We couldn’t run a disk, destroy the residue and then no-till with any kind of improvement. We didn’t realize how much we needed roots year-round.”

Second was dispelling myths about fertility. “Everyone said no-till was losing fertility and that fertilizer was running off or laying on top. Glover and agronomist Al Baxter took some of the first measurements and found it did move down a couple inches and could move through the profile as much as 8 inches. We learned that we were improving the profile.”

Impact of Industry Support & Teamwork

New Chevron Chemical (now Valent) employee Bill Haddad heard of no-till at a company meeting in 1969. After seeing what mule-operating Amish farmers were accomplishing via no-till in one day, he realized his calling would be tied to the fledgling practice. After 4 years with no-tillers in the Mid-Atlantic states, Haddad accepted a transfer to help grow no-till in Ohio in 1973.

Haddad’s experience and connections from the east, where no-till was succeeding, came in handy. In the mid-1970s, Cornell University soil scientists asked to spend 4 days at OSU. Triplett assigned him the task of preparing an itinerary. “Thirteen scientists showed up, and we ran them out to numerous fields and farms in vans – without AC in those days – in 90-degree heat. They saw their first no-till soybeans. They came back twice more, and we were invited back to Cornell, too.” The cooperation expanded to other states with joint meetings that would attract as many as a dozen universities at once, he recalls.

The persistent Haddad was known for his tireless work to help farmers with slugs (including unauthorized recipes that included beer), weed control and homemade equipment. He also replicated 1940s-era earthworm studies to show farmers the unseen advantages of the new no-till method.

Haddad and Triplett were constantly venturing out for the on-farm demos and field days needed to change hearts and minds, says Reeder. Haddad invested his own funds in the state’s first Spra-Coupe sprayer to demonstrate effective weed control systems for no-tilled crops.

“We thought within 5 years there’d be wall to wall no-till. But it’s hard to change people’s minds, especially farmers. We took a lot of shellacking over no-till.”

Universities were a problem, he recalls. “The universities were so worried about their reputations. Michigan and Indiana were very negative on no-till. West of Ohio, they didn’t believe in it.” He recalls cornering a naysaying professor from Michigan on a bus tour and “working him over” since he couldn’t escape.

Haddad (“an innovative educator,” says Reeder) and Chevron organized a program in the 1970s that recruited 8 farmers to consult with the company. Each of the farmers, including No-Till Farmer Legend David Brandt of Carroll, Ohio, was required to host an annual field day and give three talks. “This expanded farmer-to-farmer experience,” says Reeder.

When Chevron’s program ended in 1980, Monsanto and Dow Elanco picked up the mantle. Brandt continued with Monsanto as one of 40 no-tillers who met twice a year to offer advice and feedback, and to train other farmers.

Haddad says industry support was key. “Chevron had funding and a salesforce that helped get equipment into farmers’ hands,” he says, citing the Midland Zip Seeder, Lilliston and Haybuster drills as well as Allis-Chalmers and White planters. “If not for their support, no-till wouldn’t have gone as fast.”

After Triplett retired and then joined Mississippi State University in 1983, the partnership with Chevron/Valent continued. Valent Sales Rep Neil Badenhop says that Triplett taught many future employees in the Mid-South throughout the 1980s-1990s.

Haddad saw great change during his career. When he moved to Ohio in 1973, the state’s no-till acres stood at 123,000. When he retired in 2016 after 4 decades of no-till work, Ohio’s no-till acreage exceeded 4 million.

Richards said the federal policies that followed were made possible by the understanding coming out of OSU.

Triplett and Van Doren’s initial 4 questions were largely answered over time, says Dick. “The first 10-20 years of this study by Triplett,Van Doren and others indicated that the problems were solvable.”

Dick added a couple more observations. “Getting good stands, especially for corn, in the no-till plots was sometimes a problem in the early years. Also, one year we had severe slug infestations in the no-till corn plots; they survived the winter under the residue. The entomology department provided me with an experimental slugicide. We applied it one afternoon, and the next morning many of the plants had a shiny sheen about them from the mucus the slugs had shed to try to protect themselves. It solved the problem, and the corn developed well.”

And then there was the impact on soil health. “We found that the long-term plots are creating a soil layer that is beginning to mimic a natural forest soil,” says Dick. “The carbon buildup extends deeper into the soil profile with time as earthworms and plant roots enrich the soil starting from the top down. This transformed soil layer, rich in organic carbon and nutrients, has many benefits both from a crop production and environmental standpoint.”

INSPIRATION AT WORK. Glover Triplett was exposed to “sod seeding” while a grad student at Mississippi State University and contributed to the development of the grassland drill. It was produced by Taylor Machine Works and John Deere but didn’t catch on because of the lack of weed control products. David Hyder

Reeder adds that the same no-till research plots across three soil types (including the South Charleston site that came later) were also key. “Having research results at more than one location, including negative results at Hoytville, gave more validity to the research.”

Engaging With Farmers

Richards recalls that Triplett was quickly understanding no-till’s nuances and publishing results. “He gave us the confidence that this all can be done. When everybody else was laughing at it, we had a smart, educated scientist showing us how to make it work.”

Richards also pointed to a farmer group put together by OSU agronomist Larry Shepard. “He believed what we needed was a bunch of farmers who’d try out new ideas, but who wouldn’t hold it against the university if they didn’t work.

“He called our group the ‘Way Out Farmers.’ Glover came one night and said, ‘You guys farming all that level land ought to be looking at these hills because with no-till, you can grow as good of corn on the hillside as in the expensive high-rent district.’ He got all excited about that.”

CURIOSITY AT WORK. A 50-cent ticket to view OSU’s no-till corn demonstrations drew 18,000 in the early 1960s. Ohio State University

Richards says the group continued meeting several times a year and reorganized under a more sophisticated identity as “Top Farmers of Ohio.” It still operates today with 75 members who get access to research for soybeans, corn, insecticides and weed control.

“Glover focused on what no-till was going to do for the smaller farmer, who wouldn’t need tillage equipment and could plant with four rows and a little tractor,” says Richards, who surprised Triplett by moving to the massive scale that he did in the 1980s.

Influence & Impact

If Herndon, Ky. was ground zero for commercial no-till, OSU must be regarded as ground zero for no-till research and science.

By 2012, the number of published studies from the OSU plots in the first 50 years totaled 70, a number close to 100 today. “And then all the other universities who’ve taken soil samples,” Reeder says. “Warren Dick used to joke about the amount of soil removed from those plots, one soil core at a time.”

MODIFIED PLANTERS. With the help of ag engineers like Dr. Bill Johnson who modified planters for no-till, Glover Triplett (pictured) conducted pioneering no-till research at OSU before “retiring” in 1982 and joining Mississippi State University a year later. Mississippi State University

When asked of the global importance of the OSU research plots, Dick points to the scientific citations. Dick says that Google Scholar reports that the top three papers on which the OSU plot data was based represents 1,697 citations alone. “It’s safe to say these plots have generated more citations than any other such plots,” he says.

Fast-Tracked Knowledge

All agreed that the no-till tide would become unstoppable once the herbicides and planters arrived that could make no-till work. But they agree adoption would’ve been slower without OSU’s studies that boosted farmers’ confidence and managed the risks.

“Many university extension services were saying that while no-tillage might work in lighter soils, don’t try it in heavier soils…”

“Glover and Dave pushed the technology forward much faster because of their efforts and the research plots they created,” says Dick. He ranks their 1977 “Agriculture Without Tillage” paper from Scientific American right up there with the famous 1943 book Plowman’s Folly by Edward Faulkner. “These materials got the idea into the mainstream public that crops could be grown without tillage and actually offer benefits compared to full inversion tillage.”

Richards says Triplett kept him and others on the right path. “There were years we took a yield loss. But Glover’s work said what we were doing was scientifically correct. It kept me going knowing we were right – or that we would be in the long run. To have an educated friend that kept encouraging us was awfully important.”

Due to OSU’s work, Richards says that even with his experience in reduced tillage, he’d been given at least a 5-year head-start in no-till. “When Glover opened our eyes to the idea of the no-till coulter, that’s all we needed. And then we took the horsepower requirement out of planting and that opened us up to 60-foot-wide toolbars thanks to Jon Kinzenbaw (Kinze) and John Deere’s self-driven units. That just allowed us to explode.” By the 1980s, Richards would be no-tilling 8,000 acres.

Without Richards’ early success in no-till, he couldn’t have taught the practice to Peter Myers (also an NRCS Chief) and Jim Mosely, both of whom later served as USDA Deputy Secretaries. And without that, perhaps a conservation title isn’t woven into the 1985 Farm Bill. And without the conservation requirements and the need to get a “real farmer” to convince others of no-till’s merits, Richards doesn’t end up in Washington, D.C. in 1989 to extol soil conservation to the masses.

Keeping the Support

American no-tillers are lucky to have several long-term no-till plots, says Reeder. “Often, after 3-5 years, a researcher writes a paper and moves on to something else,” he says.

Successful long-term research requires a dedicated team, from the farm workers to faculty members to administrators, says Reeder. More so than the financial commitment, says Dick, are the details that must be put into scientifically-sound planting, harvesting and coordinating requests for access.

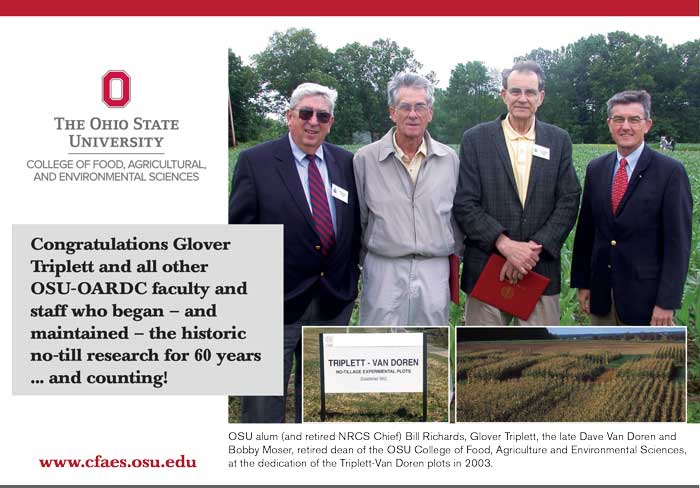

Dick had the foresight to establish a fund, endowed by Triplett and Van Doren, to manage the plots. In 2003, they were rededicated as the Triplett-Van Doren No-Tillage Experimental Plots.

.jpg)

Asked why OSU received continued support when other universities didn’t, Reeder nods to Triplett. “He was so persuasive and was dedicated to no-till. Plus getting that converted planter out on farms so they could see how it was working – that built interest around the state. It wasn’t viewed as just a research project. Getting the no-till planter out of research plots and onto real farms sped up the development.”

Dr. Leonardo Deiss has since taken over the OSU plots. “He is very interested in maintaining these plots and gleaning as much new information as possible from them,” says Dick. “But his position is not a tenure track position, so the plots’ future still needs to be emphasized.”

For More Information

For more on Ohio State’s History-Making No-Till Plots, click on the links below:

• Influencing World’s Understanding of No-Till

• Failure Was Never a No-Till Option

• [Podcast] Glover Triplett and the Early Days of No-Till Research

• [Podcast] Breeding Success in No-Till with “No-Till Bill” Haddad

• [Video] Ohio State University’s Pioneering No-Till Research Since 1962

• Profiles in Passion: No-Till’s Proven Template for Changing Ag

• Ohio State No-Till Research from 1962-2012

• A ‘Who’s Who’ of Ohio State No-Till – coming soon

• [Video] Triplett-Van Doren Plots Walk-Through by Dr. Deiss

Much Left to Learn

A few years ago, No-Till Legend John Baker of New Zealand asked a Western Illinois University audience how it would rate the current state of no-till knowledge. “The audience settled on 50% and I agree,” Baker says. “In other words, in 60 years, only half of the knowledge of the system has been uncovered.”

Reeder maintains the plots need to go on for another 60 years because there’s so much yet to discover. He cites cover crops as an example of extensive and significant “new” knowledge gained over the last 10-15 years alone.

“There isn’t any reason to think that we won’t continue finding improvements with no-till,” he says. “Suppose 100 years from now, almost all the cropland could be in some form of no-till with a perennial cover crop. Somebody might look back on this 100 years from now and see the impact of no-till on global climate change.”

At age 92, Glover is still “dialed in” and asking for updates on the no-till plots. He’s also still apt to share teachable moments with an ag editor on earthworms and erosion. He’s also keenly aware of today’s regulatory issues on atrazine. “We’ve got other herbicides, but I hope the government doesn’t mess with this to the point that it makes us go back to plowing.”

The 2024 No-Till History Series is supported by Calmer Corn Heads. For more historical content, including video and multimedia, visit No-TillFarmer.com/HistorySeries.

Post a comment

Report Abusive Comment