We started no-tilling in 1983 and are still on that path today. For years, we’ve incorporated cover crops and now we’re using multi-species cover crops to protect the soil.

We’ve found that doing this increases water infiltration and water-holding capacity. The soil acts as a natural sponge or a filter to prevent soil from running off and ending up in the Great Lakes. My focus is not only on soil, but on water quality. As a Nuffield scholar, I was given the opportunity to travel the world to study how to conserve farmland with cover crops, and the importance of biodiversity.

By the year 2050, there will be 9 billion people on the planet and the question arises: How do we feed all of them? What upsets me is that in the conversations to answer this question, water is never brought up.

We are told that we need to feed the world but if we don’t have water, we won’t have a crop. By 2025, 1.8 billion people in the world will face water scarcity — that’s 1 in 4 people living on our planet. I believe the only way to have clean and healthy water is to have healthy, living soil.

Learning Abroad

Through my travels, I have had the opportunity to visit farms in in countries including Mexico, Chile, Brazil and Argentina.

In Obregón, Mexico, I visited CIMMYT, which is the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Centre. CIMMYT was the brain child of Norman Borlaug. He was focused on providing seed genetics for impoverished nations, as well as advancements in phenotypes for both corn and wheat.

In the desert, the contrast between where there’s water for irrigation and where there’s no water is like salt and pepper. Where you have no water, you have no crop. Where you have lots of water, you have a crop. The real dilemma for a country with high population density is this: Do you use water for human consumption or for crop production?

In Mexico, they used an electric shovel to measure root phenotypes. In the desert, when you have longer roots, you can extract more water. You can then increase the exposure in the soil profile. The correlation between length of straw and length of roots is a direct 1:1 ratio.

What I’m finding at home is that seed companies keep shortening the straw length of wheat varieties because all the farmer wants is the grain; he doesn’t want the straw. As they shorten wheat varieties, they are actually limiting the amount of soil and water that is accessible.

While in Chile, I visited with Carlos Crovetto, one of the greatest no-till pioneers in the world. Crovetto is all about “grain for man, straw for the land.” The straw needs to feed the soil microbes which are the living food source for all the biology beneath our feet.

When at Crovetto’s farm, he made me slow down and think. He would walk with his hands behind his back, his head down and he would say, “Friend, let me tell you something. It is all about the carbon. The carbon is the food, the food for the soil.”

Thousands of visitors come to his farm to learn what he’s doing. When you grab ahold of his soil and rub it between your fingers, you can feel the grease, the microbes. Crovetto isn’t farming the most robust soil. He’s actually farming some B and C horizons. When farmers tilled hundreds of years ago using animal horsepower and tilling with the slope, all the topsoil eroded off the landscape into the river and out to the Pacific Ocean.

EROSION ISSUES. Blake Vince says he learned a lot from Chilean no-tiller Carlos Crovetto, who once told him, “Friend, let me tell you something. It is all about the carbon. The carbon is the food, the food for the soil.” Some of what Crovetto farms is B and C horizons due topsoil eroding from the landscape long ago into the river.

Sadly, Crovetto is one of the few remaining farmers in his area of Chile. When I traveled across North America and when I traveled home, I saw a similar topography to that of Chile. Now we’re using machine horsepower and tilling with speed and aggressiveness. It’s quite possible that we’re going to erode our soils even faster than what happened to the Chilean landscape.

In Brazil, they produce 2.7 crops per year of corn and soybeans. Brazil competes with North American farmers in the global marketplace. When we talk about Brazil, most people say, ‘They don’t have infrastructure.’ I’ve traveled to Brazil where I saw very elaborate infrastructure-handling facilities.

I was on a farm that produced coffee. They planted coffee in a circle to utilize pivot irrigation. What was more fascinating was that they took 1,300 acres out of production and flooded it to utilize as their own water source.

That resonated with me because we farm that much acreage at home and I saw my entire land base under water. It made me feel like an insignificant individual.

While in Argentina, I visited farms in a rain-limited environment. They plant corn hybrids that are selected for multiplicity. With these hybrids, plants consistently produce more than one ear.

On a rain-limited year, there’s one dominant ear that forms, but on a year where there is adequate precipitation there are two nice ears. Having the two ears means they can drop their seeding rate and limit their downside risk.

There are several benefits to multiplicity: less water usage; decreased planting population (lower seed cost); lower nitrogen (N) requirements, and increased yield predictability since higher populations result in lower yields.

Lessons Back Home

On our farm, we have 1,200 acres and grow corn, soybeans, winter wheat, cereal rye and cover crops. Our soil is glacial lake-bottom. It is Brookston clay and classified as imperfectly drained.

Tile drainage is of paramount importance in our geography. Most farmers still actively till and the moldboard plow is one of the commonly used tools. Farms are tilled bare, with little stubble retention for winter. The “stale seed bed” method is still widely practiced.

TOUGH SOILS. Blake Vince describes soils in his region as “flat as a pancake” — glacial lake-bottom Brookston clay and imperfectly drained. When winter freezes the subsoil and a rapid thaw event ensues, coupled with rain, water lays on the soil surface and flows to the ditch instead of infiltrating. He’s battling these conditions on his farm with cover crops to increase organic matter, improve infiltration and water-holding capacity.

Our topography is flat as a pancake. During winter, when the subsoil is frozen, if we have a rapid thaw event coupled with rain, the water lays on the soil surface and cannot infiltrate down through the profile, so it releases and flows to the ditch. This is contributing to nutrient runoff going into the Great Lakes.

Great innovation always happens at the farm level. I use an old John Deere 7000 corn planter with a row mounted rolling basket that we implemented when strip-tilling.

When I used to strip-till, the rolling basket worked well to take air out of the zone. Our soils can be very colloidal when tilled, so we were basically destroying soil structure. The row basket would smooth the strip tilled zone and allow the planter row unit to run smoothly across the field.

Today, it’s become a great addition to roll down the cover crops to allow the double-disc openers to open the seed trench and plant the seed.

Having traveled around the world, I had the confidence to bring what I had learned to my farm. I didn’t invent the wheel, but I had the opportunity to learn from great minds, so I went home and I implemented the no-till, cover crop system.

First, I started off with a five-way cover crop mix and I’ve continued to build upon that. In an 18-way cover you’ve got legumes, flowering plants, grasses and all kinds of living things.

I’ve farmed with my father and uncle my whole life. Each generation has done it their own way. My father grew up in the no-till environment, so in his mind you need to kill everything that is green before you plant the seed. When I came home from my Nuffield travels, I decided we were going to do things differently.

I think our soils are addicted to N, so you cannot go from hero to zero. When using nitrogen, we have to wean our soils off gradually. My Dad, being old school, still wants to have 1 pound of N for each bushel of corn.

GOING GREEN. Blake Vince says his father’s philosophy was to kill everything green before seeding. But Vince did it his own way, no-tilling green beginning in 2014 (left) and ramping up the practice even more in 2016, saving money on nitrogen and improving soil biology.

In 2015, I lost yield to my father by using about 0.6 pounds of N per bushel, but when we laid the financials on the table the net profit was identical. He had more yield but I saved the money up front on N. Each year we’re increasing the acres that we’re planting green. Our fertilizer tanks on the planter are empty and we apply it in the summer after wheat harvest.

I spread fertilizer according to soil test results and plant a cover crop to grow and keep the soil covered. I always want to have that living green plant and a living root.

By June 15, 2016, 3 weeks post planting, we’d only had 2 tenths of an inch of rainfall. We had gone from a wet, cool spring to a situation of drought and high temperatures.

My corn stayed green in 2016 when everybody else’s was firing right up to the ear shoot and beyond. It wasn’t the biggest corn crop I ever harvested in my life, but it wasn’t the worst either and it helped me learn a lot. I’ve learned way more from my failures than I’ve ever learned from my successes.

Why do I get excited about what I’m doing? Because I can use less N and zero tillage. I can protect my soil from erosion from wind, water and, the least discussed, solar erosion. We can increase biological activity. We can capture solar energy for 12 months of the year. We can increase our water infiltration and increase our water-holding capacity. Most importantly, we can increase our financial yields.

Water and Soil

One of my favorite pastimes is ice fishing for walleye on the local Thames River. Normally in July, the river looks like chocolate milk. In the winter, when I’m ice fishing, sitting on my bucket and I look down into the clear water, I can easily watch my lure descend several feet into the water column.

I remember a period 2 weeks after a rain event last December where there was water on the soil surface of area farm fields. There was some water running off into the ditches, so I know that there was active soil movement at that time, tiles were still running and the water was clouding in the Thames.

But after 2 weeks of freezing temperatures, the water clarity improved dramatically — so much so that I said, ‘I’ve got to capture this for my Rotary friends because they won’t believe this.’ We’ve all lived in this environment and I’ve told them different times and said, ‘You should see the water underneath the ice in the winter. It clears right up.’ You know what they say to me? ‘I don’t believe it.’

I got a sample and it looked like clear water in a glass. I then showed this to the proprietor of the business, which happens to be along the Thames River, where our Rotary club has met for years. She was in disbelief because this was not the Thames River she was used to seeing.

What’s at Stake

I believe that as farmers we have great stories to tell. This work we’re doing towards healthy soil which equals healthy water can have a huge impact. If we’re going to influence change we must put agriculture in the best light possible.

We started the Clean Water for Living Series because Rotarians at home heard me talking about the importance of water and how we ignore it in North America because we take having available fresh water for granted.

When I started down this path, I was told I was not a phosphorous (P) expert and I should stand down. I’m not a P expert and I never professed to be one. However, I am a concerned citizen so don’t I have the right to voice my concern? Albert Einstein said, ‘Those who have the privilege to know have the duty to act.’

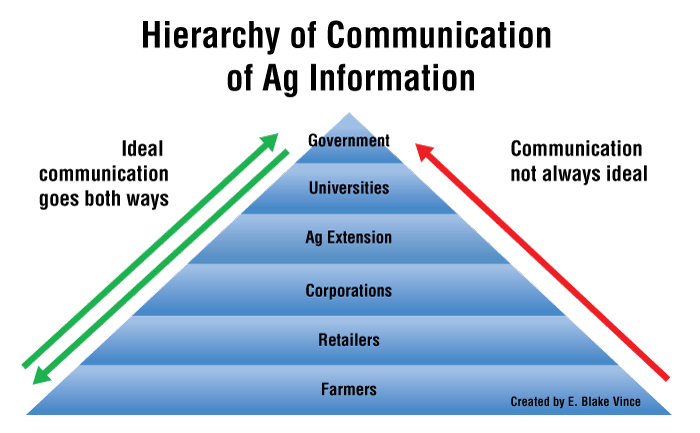

I view today’s agriculture in terms of a pyramid: from top to bottom, we start with government, then universities, followed by ag extension, corporations and retailers, and then we’ve got the farmers at the bottom.

FIXING COMMUNICATION. No-tiller Blake Vince believes changes might be enacted more quickly to improve water quality in the Lake Erie watershed if information flowed more freely back and forth between farmers at the bottom of the communication pyramid to government agencies at the top, rather than the top-down approach currently in use.

When the information flows, in an ideal situation, it flows from top to bottom, bottom to top, and that’s how it should work. Sadly, there’s a lot of top-down information from the government.

Unfortunately there are individuals — the innovators — that try to take information and help everyone get to the next level and bring it up from the bottom level (the farmer level to the top). Sadly the farmer opinion is not always welcomed.

Lake Erie is a federally regulated resource on the Canadian side of the border. The provincial level is required to implement the changes, and then you’ve got your regional conservation authorities that are involved in administering some programs too.

There are levels of bureaucracy similar to the U.S. because every state that borders on Lake Erie has their own policy pertaining to shared freshwater resources.

What we do to the soil and products we use on farmland such as fungicides and insecticides, all have an effect on the living things that interact with the land, from insects and birds to fish and even livestock. The water, too, is affected. It’s all interconnected. The water that comes in from Lake Erie affects me and my family.

It has been well documented that in water bodies with blue green algae there are neurotoxins. This is true for freshwater sources like Lake Winnipeg. These neurotoxins have links to neurological diseases like ALS, Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s.

So, do you think it means something to me that I want the water that comes into my home via the municipal water line to be the best quality possible? You bet it does. Sadly it gets swept under the carpet, because we have to produce a crop, we have to stay in business, we have to feed the world. But if we don’t have clean water, we won’t have to worry about feeding anybody.

It’s all about soil: everything else doesn’t matter. It’s not about the attachments, it’s not about the machinery, it’s not about the seed, the chemical, the fertilizer. It’s about getting back to the soil first, and everything else will fall in around that.

Remember, we belong to the greatest profession, the profession that everybody needs three times a day, morning, noon and night.

Post a comment

Report Abusive Comment