Pictured Above: READY TO GO. Bags of cover crop seed are prepared for shipment from Saddle Butte Ag’s warehouse in Tangent, Ore. The majority of no-tillers surveyed by No-Till Farmer know the retailer of the cover crop seed they’re buying, but few know where it was grown.

John Stigge knew something wasn’t right when the cereal rye he drilled into a moistened field didn’t come up — even after irrigating the field twice to a depth of 1 inch.

The irrigated rye should have been a “slam dunk” for fall grazing, he says, but the rye did nothing in the fall, causing an untimely reduction in options for grazing for his cows and calves.

“When I questioned the regional seed dealer he finally admitted he had no idea what variety he had. He said, ‘Rye is rye, as far as I can tell,’” Stigge recalls. “I’ve found that the variety of cover crop is more important than the type of seed itself. I couldn’t rely on the suppliers for information because I knew more than they did.”

As adoption of cover crops in the U.S. has nearly tripled since 2010, the number of companies selling seed to farmers has also increased. Even though much of the evidence is anecdotal, some observers say complaints about cover crop seed quality and variety issues are increasing.

Companies selling cover crop seed in the small-seed industry aren’t required to certify their product and are mostly free to procure and market seed as they see fit. The seed growers, breeders and testing labs are mostly unknown to growers.

No laws require cover crops to be tested in all the states into which they’re sold. And when gaps in supply for certain varieties of covers occurs, companies might choose to replace them with varieties that are unsuitable for certain climates — sometimes without a grower’s knowledge.

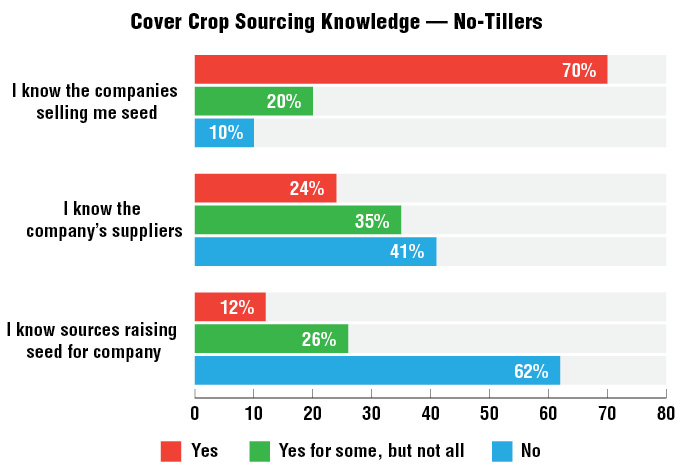

Some say the reliance on self-policing in the cover crop industry has opened U.S. farmers up to exploitation. Last month, No-Till Farmer surveyed readers on what level of knowledge they had about the source of their cover crop seed, and among the 250 who responded, 62% didn’t know the original source for their seed.

Readers also shared problems with seed they purchased that couldn’t be explained away by poor management or weather issues — poor or no germination; weed seeds present; unsuitable varieties mixed in; unanticipated species in a mix, or the wrong ratio of species; diseases or insects carried over in seed; different growth patterns; poor grazing quality; and hard seed.

Lax Enforcement

There are two major federal laws that impact the cover crop industry — the Federal Seed Act, which requires accurate labeling and purity standards for seeds in commerce and prohibits the importation and movement of adulterated or misbranded seeds.

The Plant Variety Protection Act (PVPA) is a voluntary program that provides patent-like rights to breeders, developers and owners of plant varieties. PVPA gives breeders up to 25 years of exclusive control over new, distinct, uniform and stable sexually reproduced or tuber-propagated plant varieties.

State departments of agriculture also have a hand in policing issues with mislabeled cover crop seed, but they might not step in unless a certified variety is involved, says retired University of Illinois agronomist Mike Plumer*, a conservation consultant who does cover crop research and works with Midwestern growers on establishing covers on their farms.

There are already laws on the books in most states that address seed quality, such as requirements for certain information to appear on the label accompanying each bag of seed. Depending on the state, seed offered for sale should be labeled with information on the kind, variety, purity, germination, lot identification and the labeler’s name and address.

But Plumer has seen cases where companies have sold seed that came from different lots, but only one lot number was used on all the bag tags. He once caught a farmer who was printing his own tags to place on bags.

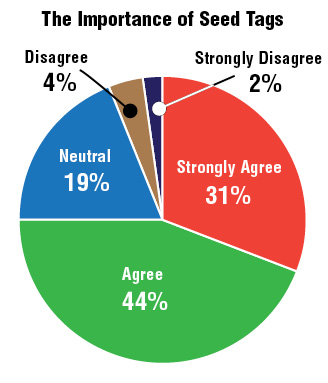

Growers apparently do want more information on what they’re buying. Recently the American Seed Trade Assn. (ASTA) sought insight into the importance of seed tags in the cover crop market, and asked farmers if it was important to see information about seed purity, germination and noxious weed content before planting cover crops.

Among 1,000 respondents, 75% said they agreed or strongly agreed seeing that information was important, and 19% were neutral.

“There’s a lot more small seed sold today than there was 30 years ago, so the concept of certification now is a guarantee of what’s on the bag is what you get, and you will get the same thing year to year,” says Plumer. “Farmers often don’t know what they’re getting unless they know the company directly.”

From A to B

KNOWLEDGE GAPS. The vast majority (90%) of no-tillers surveyed by No-Till Farmer know who they’re buying at least some of their cover crop seed from, and nearly 60% know at least some of the company’s suppliers. But 62% don’t know who is raising any of the cover crop seed they’re buying.

LABELS KEY. When the American Seed Trade Assn. recently surveyed more than 1,000 farmers about the importance of seed tags in the cover crop market, 75% said they agreed or strongly agreed seeing information on seed purity, germination and noxious weed content before planting was important.

The supply chain for cover crops from germplasm to a farmer’s field isn’t widely known. But according to ASTA, it goes something like this:

- There are three classes of seed — certified, uncertified and common or VNS (variety not stated) seed. Both certified and uncertified seed are sold by variety name. Certified seed is grown under the supervision of a certifying agency and will typically have a blue tag.

- With certified seed, growers obtain permission from a breeder or contractor to produce a variety, and a contract is created. Seed stock, such as registered, foundation or breeder seed, is raised by small-scale growers. Planting equipment is to be cleaned and vacuumed out to prevent variety contamination.

- Field inspectors from seed-certifying agencies, such as crop improvement associations, inspect fields once the seedlings have emerged to ensure that there are not any off-types or contaminants growing in the field. The inspectors will visit the field again once it has headed to again look for off-types, excessive other crops and prohibited noxious weeds.

- For uncertified production, the contracting company or grower assume the responsibility that there are little to no off-types or prohibited noxious weeds in the field.

- After all inspections have been completed, the seed is harvested after it ripens and is taken to a warehouse for cleaning. Combines, trucks, wagons, grain bins and augers/conveyors and processing equipment is to be cleaned beforehand to avoid contaminating varietal purity.

- Seed samples are obtained by a representative of the certifying agency from either an automatic sampler or are pulled manually, and samples are sent to a certified seed lab for analysis. The lab generates an analysis report with information on germination and purity, noxious weed seed, inert material and other parameters that is sent to the seed grower.

- If other varieties show up that aren’t part of the advertised product, or too much weed seed or inert material is present, the seed could be demoted to “Variety Not Stated” or “Common” status.

- Foundation, registered or breeder class seed then goes to large-scale commercial growers for multiplication. After proper inspection, harvested seed is cleaned and processed again with screens and high volumes of air to remove seeds that are larger or smaller than the desired size, removing inert matter such as leaves, stems, insects and weeds. Then the seed is packaged, labeled and stored for sale.

- Final seed samples are sent to a lab for analysis to ensure purity meets certified standards and are within allowed tolerances permitted on the label. A lab report is sent back to the seed grower, and the breeder or contracting seed company is copied on the resulting analysis certificate.

- Once the seed has met the contracted or certified quality parameters, the seed is delivered to a wholesale dealer that will sell the seed through their distribution channel to an ag retailer or farmer.

Tales from the Field

Stigge has been seeding cover crops on his no-till operation near Washington, Kan., for 23 years, using many different species in his mixes for forage and to improve soil health.

CUTTING LOOSE. A worker at Oak Park Farms in Shedd, Ore., cuts turnips in mid-June, windrowing the plants and letting them cure for 10 days before they’re harvested for seed, says the company’s president, Mike Coon.

With covers he’s encountered problems with poor germination, different growth patterns, disease carryover, different varieties, no winter hardiness when he wanted the cover to overwinter, poor grazing quality — which he describes as a “huge problem” — as well as allelopathy differences.

The aforementioned cereal rye that didn’t emerge in the fall came up in spring and bolted with a vengeance, degrading in feed value once it reached the boot stage.

Stigge has also been frustrated with annual ryegrass, noting that he’s only found two varieties out of several he tested that both consistently overwinter and provide deep rooting. He needs to have some predictability with his cover crop program, as he doesn’t have cattle pens and animals are out in pastures all day roaming.

“I ended up going directly to a grower in Oregon to get the annual ryegrass that is so important to my program, thus eliminating the problem of variety switch seed dealers,” he says, noting he doesn’t advise other farmers to do this due to the expense. “I looked at several farms and found one that is very progressive with its breeding program. This enabled me to have a repeatability as much as Mother Nature will let us have.”

Ralph Stonerock runs a conventionally tilled organic operation near Marysville, Ohio, but has been seeding cover crops for the last 7 years to improve organic matter in his soils. Getting quality cover crop seed from Ohio or Pennsylvania hadn’t been a problem, he says, until last year when he ordered a mix of oats, radishes, crimson clover and hemp from a company advertising the seed as “organic.”

When Stonerock pulled back the shrink wrap the first thing he noticed were live weevils crawling around.

“I took photos and sent it back to the guy who sold it to me, but they didn’t do anything other than say, ‘Well that’s just organic.’ I said, ‘If that’s just organic then I don’t want it,’” Stonerock recalls.

Already running behind in getting cover crops seeded, Stonerock went ahead and planted the seed in late August rather than taking a 2-week delay to get replacement seed. A few days later, numerous weeds emerged with the covers. A microscopy showed a large amount of foxtail, giant ragweed and waterhemp seeds had been in the mix.

“I had to tolerate it — there was nothing I could do about it,” Stonerock says, noting he had to spring disc the field a few times this year until the weeds were pulverized and he could plant corn. He dealt with the insects by mixing the seed corn with beauveria bassiana, a fungus that grows naturally in soil, that served as a pathogen to kill the weevils and larvae.

Clark Porter, who minimum-tills corn and no-tills soybeans near Reinbeck, Iowa, says cereal rye is the workhorse cover in his latitude and climate, and he recently tried a combination of cereal rye and winter wheat and got good coverage. But there have been downsides as well.

“It’s always tough to tell, but I think weed seeds have been the biggest problem,” he says. “Since I began cover cropping I’ve seen more Canadian thistle. I’ve been mowing and spraying to control it, but so far the thistle is winning. This year I’ve had large patches of giant ragweed too. It came on so fast, and in such diverse spots, that I am suspicious of the cover crop seed.”

Despite of the weeds, Porter says he’s still a strong advocate for cover crops and he’ll keep seeding them.

Steve Ford, a no-tiller who operates an organic farm near Courtland, Ala., says he’s noticed winter peas in fields this year that likely came from a previously seeded cover crop, as well as unwanted vetch that might have come from a local source. He is concerned other things could show up sometime.

“Since we’re trying to do no-till organic, any weed seed that ends up in our cover-crop mix will be a big problem. We need weed-free guarantees,” he says.

Lack of Knowledge

Most no-tillers initially blame poor cover crop performance on factors like weather, poor seed-to-soil contact or poor management because performance problems are hard to prove, Plumer says. “The only way to prove it’s performance is to have one or two known varieties in the same field, planted at the same time,” he says.

SCOUT TIME. The seed heads of a fescue plant are checked by an employee at Oak Park Farms to see if the crop is ready to be cut. Grass seed at the facility is generally cut between 35-50% moisture, depending on the type of grass seed, says president Mike Coon.

“There is a lot of misleading advertising in small seeds,” he adds. “One company came to Illinois a couple of years ago touting winter-hardy annual ryegrass. So I bought it for trials and it wasn’t winter hardy at all. It had less than 10% survival. It came from Tallahassee (Florida).”

Another issue is the popularity of bin-run seed being used by no-tillers as a cheap way to get covers seeded. Sometimes the seller has no idea where the seed came from and cannot provide accurate information to growers, Plumer says. The sellers may also be violating the law, as seed sold commercially is supposed to be tested.

“Cereal rye sometimes is simply rejected grain that can’t be sold in the market. It may be low quality, or have diseases or low germination, and a lot of inert material mixed in with it. But since there is no regulation, nobody knows what they’re getting until they get it,” Plumer says. “I’ve received cereal rye myself where the tag said it was 90% germination, but it germinated at less than 10%.”

Some problems have been reported recently with rapeseed. Some growers raising what was supposed to be dwarf-Essex rape watched it grow 6-7 feet tall when it was only supposed to be waist high, Plumer says.

When a certain variety gets very popular a company might not be able to meet demand, “so they buy seed from wherever they can get it, put a brand name on it and sell it,” he says. “As long as it’s a brand name and not a specific variety, and it’s not certified, it doesn’t matter. It could be 1 or 20 different varieties, as long as it meets germination.”

Value of Blue Tags

Although companies acknowledge there can be problems with cover crop products, they note the cover crop industry is still fairly young and there are some issues to be worked out.

Even though a more dedicated certification program for cover crops has been discussed among ag stakeholders, the number of prominent companies selling certified cover seed with “blue tags” to row-crop farmers appears to be fairly small.

Don Wirth, co-founder of Tangent, Ore.-based Saddle Butte Ag, says his company goes through the certification process for some cover crop species, but doesn’t advertise that fact because customers aren’t currently willing to pay a premium to get certified seed.

He also doesn’t believe the cost of certification provides consumers with any security. He notes some universities are churning out brands rather than specific varieties that are approved with the PVPA because brand names are good indefinitely.

“I believe the reputation of a company is more important than a third-party tag because the third party doesn’t know what seed was planted — only that it looks like the third party thought it should when they did a field inspection. And you can’t prove what seed was put in a bag that the tag was hung on,” he says.

“I would challenge anyone to get a blue tag and read the back of it. When you read all the disclaimers, what do you have besides a piece of blue paper?”

Companies also tell No-Till Farmer that knowing what cover crops to stock from year to year, and fulfilling all requests with the exact varieties requested by farmers, can be difficult because there is no forecasting system available and farmers often wait too long to order.

Sometimes substituting a variety for the one the farmer requested originally is unavoidable, says Scott Wohltman, cover crop lead with La Crosse Seed, based in La Crosse, Wis.

“To be profitable and sustainable we have to have flexibility on what we bring to the market because we have no idea what will be requested from year to year by growers or the industry as a whole,” says Wohltman, who is also a current chair of ASTA. “There are going to be issues in some years where you can’t get certain varieties, or perhaps enough supply of new varieties. We do make substitutions and corrections known to our dealers.

“However, because we rely on ag retailers and seed dealers to communicate our message on agronomics and management to the end user, we seldom communicate with farmers. That’s not our channel to market. We have nothing to hide.”

Nick Bowers, director of operations at Harrisburg, Ore.-based KB Seed Solutions, says supply hasn’t been an issue for his company, and this summer is the first in a decade where they haven’t had leftover seed. The company has grown certified seed in the past, but found few customers were interested in paying for it.

“We just haven’t offered it because our customers have been happy with uncertified seed,” he says.

“I think, in a lot of ways, we’re still in a preliminary timeframe of developing the cover crop business, as a practice,” says Mike Coon, president of Oak Park Farms in Shedd, Ore., noting the company bought its own seed cleaner in 1970 and does all the work in house.

“There are a lot of different things that can be grown as a cover crop and it’s amazing to me how many different microclimates there can be. So to try to develop knowledge quickly on what goes where and what mixes work, and get them into the correct place, is quite a challenge. Some species, such as radishes, are adapted to a pretty wide area, but some other things may not be.”

Know the Facts

Here are some additional questions Plumer suggests no-tillers ask when purchasing cover crop seed to hopefully decrease the chance of getting burned:

- Do you sell seed in my area, and what are the names of local farmers buying seed from you, so I can check on the results?

- Is there a guarantee on variety purity, or is it a brand where there’s no guarantee of anything?

- Ask that the seed be lot-number tested for every seed tag. What’s the lot number, what date was it tested, and which farm did it come from?

“If they can’t tell me who raised the seed and where it was raised, I’m worried,” Plumer says.

“If it’s a quality company and there are lot numbers, they should be able to tell you where it came from.”

“Don’t buy seed because it’s the closest or cheapest source,” Bowers adds. “Find out what it is and who’s producing it and ask some questions. Maybe call a neighbor and see who they’re dealing with. Anything coming out of Oregon, whether it’s peas, turnips or radishes, has been cleaned and run through a lab, and they will know exactly what they’re getting.”

* Since this article was posted, Mike Plumer, unfortunately, passed away. Our condolences to his family.

Post a comment

Report Abusive Comment