By Andi Nichols, Oklahoma State University student and 2016 University of Nebraska Experiential Fellow

The USDA Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE) program defines a cover crop as "a plant that is used primarily to slow erosion, improve soil health, enhance water availability, smother weeds, help control pests and diseases, increase biodiversity and bring a host of other benefits to your farm." Studies from all over the world show evidence that cover crops can be beneficial to an agronomic system. While they have been known to increase yield in some cases, more importantly they can also improve soil properties that, when combined, improve soil health.

How Can Cover Crops Affect the Soil?

What exactly can cover crops do to improve "soil health?" Before this question is explored, there needs to be some clarification on what soil health means and what it entails. Soil health is a fairly new term that is loosely used and its meaning is continuously questioned by the scientific community; however, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations offers a reliable definition: "the continued capacity of soil to function as a vital living system, within ecosystem and land-use boundaries, to sustain biological productivity, promote the quality of air and water environments, and maintain plant, animal and human health."

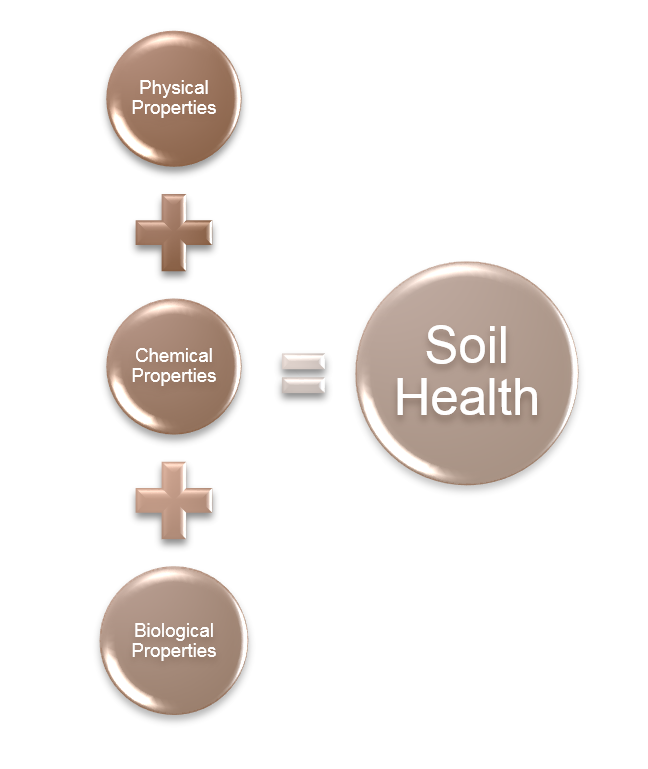

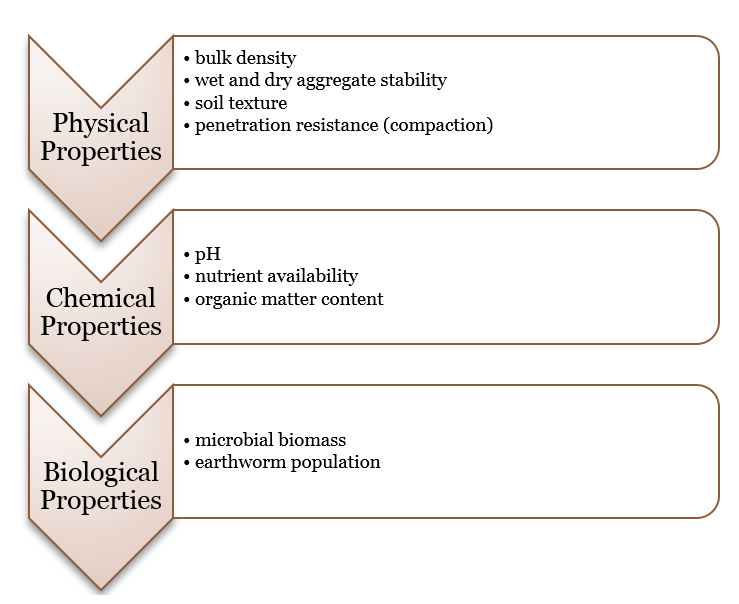

What does soil health really encompass? Many would say that it can be narrowed down to three main categories: physical, chemical and biological properties. Within each category, there are more properties (Figure 1).

Knowing the factors that determine soil health aids in gaining a deeper understanding of how cover crops can affect change. Cover crops can be implemented in a crop field to affect any of the three pillars of soil health; many times all three can be improved at one time.

For example, if a grower is interested in switching to no-till, but is aware of a plow pan in the field, specific cover crops can be selected to break through the plow pan rather than using conventional tillage equipment to break it up. Doing this could increase porosity, aggregate stability, microbial activity, nutrient availability and water infiltration. Widespread research provides evidence of the potential benefits that cover crops can yield to a soil’s overall health, but it does tend to be site specific.

An example of when a cover crop didn't significantly affect measured soil health parameters was observed during a summer 2016 case study of a long-term, diverse no-till system at the University of Nebraska's Rogers Memorial Farm just outside Lincoln.

Case Study: Rogers Memorial Farm, Lincoln

In our study we wanted to evaluate the effects cover crops had on various soil health properties. Paul Jasa, University of Nebraska extension ag engineer, has managed the study area in a no-till, corn-soybean-winter wheat rotation for the past 11 years. Three treatments were studied:

- Cover crops for carbon

- Cover crops for nitrogen-fixing

- Control (no cover crop)

Measurements were taken during the corn phase of the rotation in a field where cover crops had been rotated based on their ability to provide a source of carbon to the soil or to fix nitrogen (N). Cereal rye and grain sorghum were used as carbon sources after corn and wheat, respectively, and Austrian winter peas and soybean were used as N fixation sources, respectively, after the corn and wheat with no cover between soybeans and wheat. The experiment included evaluation of

- Organic matter content

- Macro and micro nutrients

- Wet aggregate stability

- Dry aggregate stability

- Penetration resistance

- Water infiltration

- Soil pH

- Bulk density

- “Soil health index”

- Soil moisture

Crop residue amount and weed biomass were also collected.

Most soil health indicators demonstrated no significant differences among the treatments, except for weed biomass, which was less for the carbon cover crop treatment. Water infiltration was expected to show strong differences, but didn't. It's hypothesized that this indifference is due to the higher weed population in control rows. Soil doesn't discriminate and the added plant life in control rows most likely had an impact on water infiltration rates.

Still, the data is valuable as more species are becoming glyphosate resistant. The data demonstrates that aside from cover crops possibly improving soil health parameters, they also can act as an organic weed control source, which helps lower herbicide inputs for growers and decreases weed population significantly by providing competition against the weed species.

The soil health index also showed significant differences. Soil samples were sent to Ward Laboratories Inc. in Kearney, Neb., for the Haney test. The lab website notes: "The Haney test is designed to mimic nature's approach to soil nutrient availability as closely as possible in a lab." With this test, soil gets an overall index score (numerical ranking) of how balanced and healthy its environment is. These rankings generally range from 0-50, preferably above 7, according to Ward Laboratories. In the case study, the cover crops grown for carbon ranked the highest, with a 12.2 average. Control rows were second with an average rating of 11.4, and N-fixing cover crops averaged 9.5.

Conclusion

Building on the previous definition of soil health, the United Nations FAO notes: "Healthy soils maintain a diverse community of soil organisms that help to control plant disease, insect and weed pests, form beneficial symbiotic associations with plant roots; recycle essential plant nutrients; improve soil structure with positive repercussions for soil water and nutrient holding capacity, and ultimately improve crop production."

Research has shown that cover crops have improved cropping systems in many aspects of this definition in the past. Research has also continuously demonstrated that cover crop effects are very site specific, as indicated by the research described here. The best approach to exploring the benefits of implementing cover crops is to combine research data with advice from local extension experts.

Post a comment

Report Abusive Comment