Pictured Above: SOIL LIKE A SPONGE. Mount Pulaski, Ill., farmer Jeff Martin uses no-till, strip-till, cover crops and compost extracts to attain soil that favors aerobic, beneficial microbes, mycorrhizal fungi and nutrient cycling, taking a whole system approach.

For no-tiller and strip-tiller Jeff Martin, being profitable is his number one goal.

“In the agriculture industry today, bankers, chemical reps, seed dealers and agronomists tell farmers how to get more yield, yet most farmers are struggling at making more money,” says Martin. “Nevertheless, farmers continue listening to people who tell them how to spend more, but not how to be more profitable.”

Martin’s 8,000-acre operation, in Mount Pulaski, Ill., employs 2 full-time employees and has been utilizing no-till for 25 years.

“We need to be testing everything that we do, whether it’s what we have been doing for 20 years and is conventional, or what we are doing today,” he says.

Soil Health Key to Profit

The goal for Martin’s operation is to be profitable with corn at the 300 bushel level. He views soil health as the key to profitable farming today.

How do farm profits correlate to soil health? According to Martin, growers have the wrong expectations for their soils.

NO-TILL TAKEAWAYS

-

The soil provides 17 essential nutrients to plants, but the plant needs more than 70 nutrients in the soil to make the plant successful. If those nutrients are not in balance, it affects another part of the system.

-

Healthy soil can decompose toxins, salted fertilizers and pesticides.

-

The fungi to bacteria ratio should be 1:1, but a lot of Midwestern soils have a ratio of 100 bacteria to 1 fungi.

“Far too many people in this industry look at dirt as being the medium that holds the plants upright,” he says. “The yield potential and genetic potential on a corn plant is 1,100 bushels in a perfect environment. Just because I can make 300 bushels does not mean that is my maximum profit.”

On Martin’s operation, he wants the soil to work for him. He works to activate soil that favors aerobic, beneficial microbes and nutrient cycling, comparing his soil to a sponge.

“It’s a whole system and everything has to go together to make it work,” he says. “Do the decisions I make on a daily, weekly, monthly or yearly basis support or detract from making this system work in my soils? We need to understand what soil does beneath the plant.”

The soil provides 17 essential nutrients to plants, but the plant needs more than 70 nutrients in the soil to make the plant successful. If those nutrients are not in balance, it affects another part of the system.

“We’re implementing a lot of sap testing now, which is different than tissue testing,” he says. “It gives us a reading of those 17 nutrients, giving us a better indication of what is going on in the plant. The nutrients are there, we just have to be able to access them. A healthy soil can decompose toxins, salted fertilizers and pesticides.”

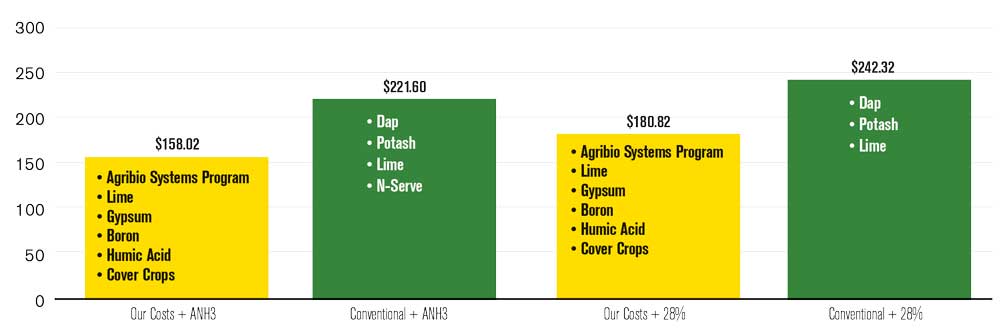

SAME YIELDS, LESS EXPENSE. Jeff Martin is cutting costs with cover crops and compost extract instead of conventional nutrients. While switching from anhydrous to 28% nitrogen increased expenses, his biologically driven system still wins out.

Growers would need less and possibly no pesticides and/or fertilizers if they focus on building soil structure, increasing water infiltration and holding capacity, increasing root depth and boosting oxygen levels in the soil, Martin says.

“We can’t do much about how much rain we get, but we can get our soil structure back up so we have better water holding capacity,” he says. “That makes us a little less dependent on Mother Nature for success.”

Focus on Fungi, Bacteria

Martin’s goal is to cut $100-150 per acre from his expense ratio.

“How are we doing this? Nutrient cycling,” he says. “We are creating available plant nutrients and the soil biology is taking those nutrients that are locked up in the soil. We are also accessing free N.”

Martin wants to achieve balanced nutrition provided solely by the plant-available nutrients. “We feel we can use this strategy to get healthy plants that are not as susceptible to disease,” he says.

Bacteria double their populations every 10-15 minutes. Protozoa feed on the bacteria to keep those populations in check.

“Bacteria has a carbon to N ratio of 5:1,” Martin says. “Protozoa has a carbon to N ratio of 30:1. Protozoa need to eat 6 bacteria to survive. When that happens, they end up with 6 N. They only need one, so they excrete 5 N into the soil.”

In turn, Martin says that plants send out a signal into the soil through their root exudates if they are low on N, silicon or potassium (K).

“This ratio exists not just for carbon and N, but for carbon to phosphorus (P), carbon to K, and carbon to magnesium,” he says. “Protozoa will eat, on average, 10,000 bacteria per day. That equates to excreting 8,000 N molecules per day.”

After doing the math, it equals 1,764 pounds of N in the soil — per day. Not to be outdone, fungi have a carbon to N ratio of 20:1, while nematodes have a ratio of 100:1.

“Nematodes eat 5 bacteria and release 4 N,” Martin says. “Conventional agronomy says this N is soluble, which is susceptible to loss, leading to nutrients and dollars lost.”

Martin says that he has seen his crops become dependent on synthetic fertilizers, which causes them to not send out the signal from the root exudates. “The synthetics will never fix nutrient cycling,” he says. “It’s a predator-prey relationship.”

Strip-Till Clears Residue

Jeff Martin added strip-till to his operation in the early 1990s. They were no-tilling corn into soybean stubble on 30-inch rows, so not much residue was left. The operation switched to drilled soybeans but had two wet springs in a row. However, it was difficult to no-till into the solid bean stubble due to the excess moisture. Strip-tilling allowed Martin to have a little bare soil that could dry out, creating a much better seedbed and stand. They could also plant earlier when strip-tilling.

“Once we started drilling beans and getting higher yields, we had a lot more residue,” he says. “We started strip-tilling to clear most of the residue, but we like to leave a little residue on the strip in the fall.”

A small amount of residue left in the strip protects the soil from winter moisture, explains Martin. In the spring, the residue is brushed away by the John Deere 1770NT 24-row planter.

“Our planter is really pretty simple,” he says. “We have Precision Clean Sweep hydraulic row cleaners, Martin spiked closing wheels, chains on the back end, nothing special. We have not used a coulter for 20 years. The soils are so mellow that all the coulter seemed to do was get down in the muck and make it worse.”

Chains on the back end of the planter help smooth out the soil. “If it is a little bit wet, the chains kind of cover that trench in a little bit,” he says.

Eight-inch wide strips are made using a 16-row John Deere 25S strip-till bar after cover crops are seeded in the fall, according to Martin, a practice the operation has been using for about 12 years. “We no-till our beans and go right down the middle of the strip. We’re getting in the same row every year, in that root zone.”

Strips are not made before no-tilling beans in the spring, a choice that Martin says has never caused a problem for the soybean seedbed. But he is considering a strip-till bar that does not have a mole knife.

Changing the configuration of the row units would allow them to get out earlier, follow the combine with a strip-till pass, and not go as deep as the mole knife, and destroy as much aggregate soil structure.

The biggest benefit Martin says he gets from strip-tilling is erosion control. In the last 2-3 years, he has been trying to make his strips on the same strip as the year before, using a John Deere GPS system and autosteer to create the strips and plant in the same spot.

“We used to move 15 inches, back and forth each year,” he says. “It is harder to do in corn-on-corn, but we are trying to go in the same strip.”

Legumes have a relationship with certain strains of rhizobia bacteria to make nitrous oxide plant available, Martin says.

“A grass crop can have the same relationship with different microbes in the soil,” he says. “Achieving this photosynthesis at 60% or greater is our goal to get 300-bushel corn.”

Too many nitrates in a crop will plug up the xylem flow system in the plant, according to Martin. Excessive N can also be a problem, because it influences where and how an insect decides to feed. Martin says he has read studies showing 90% of the P applied is in soluble form within 30 days.

“If your farm has high nitrates, that insect is going to feed in your field,” he says. “Insects can sense a sick plant and healthy plants with healthy soil.”

Martin’s operation has tried to eliminate salty fertilizers. He estimates that they will have cut out anhydrous on their farm in 2-3 years, saving money in the long run because they are not killing beneficial biology in the soil while still achieving strong yields.

“Some of the products we’ve been using have been killing our soil biology,” he says. “Our fungi to bacteria ratio should be 1:1, but a lot of our Midwestern soils have a ratio of 100 bacteria to 1 fungi. Fungi cannot live in a liquid in a jug. Bacteria can, but it will not work for fungi.”

Martin applies microfungi in a talc form that is applied to seed. After planting, he applies 50 units per acre of 28% nitrogen (N) on top with humic acid as a stabilizer. A burndown application follows 3 weeks later, including a foliar product.

“Achieving photo- synthesis at 60% or greater is our goal to get 300-bushel corn…”

He also applies gypsum, sulfur and thiosulfate. Another experiment Martin’s operation is trying is sidedressing with 28% N combined with humic acid as a stabilizer. The operation also applies liquid boron in a foliar application.

“This is not going to happen overnight,” he says. “When we first started on our program, we started taking Brix ratings, and we were at a 5. After 5 years, we are up to 11-12. We can visually see that we are doing a better job of photosynthesizing. We have to look 100 years down the road, and we have to start somewhere.

Using Compost Extract

For the past 5 years, Martin’s operation has manufactured a biological product right on the farm that is broadcast onto their crop ground, made from a compost material extracted into liquid form. The operation has its own extractor, but the extract has to be applied to the field relatively quickly after production.

“We have a couple of methods now that have extended the life to probably 5-6 days,” he says. “It really helps us break down the residue in the soil.”

“We apply 3 gallons in the spring, right in the furrow. Then we follow the corn planter with our first burndown where we apply 10 gallons of 20% and 5 gallons of ammonium thiosulphate with the chemical. Then we come back later with our second pass of chemical, if needed.”

Although unconventional, Martin says he has seen an increase in the soil biology and a 30% improvement in plant root systems, which he attributes to applying the compost tea in furrow, rather than broadcasting.

“We have had pretty good luck with it, as long as it is not extremely hot, or freezing weather for fall applications,” he says. “We either try to put it on a week ahead of or after strip-tilling, because that gives a week for those microbes to take off and get down into the soil.”

Cover Crops: Food Source for Soil Biology

Martin describes his cover crop program as a food source for soil biology, especially if the cover crop does not winterkill.

APPLYING 50 UNITS OF N. With only 50 units of applied nitrogen (N), this plot yielded 208 bushels per acre, vs. 205 bushels per acre for a plot that had 120 pounds of applied N.

The operation began using cover crops only 6 years ago, and fall weather determines how many acres are seeded with covers. The soil biology breaks down corn stalks to create a better strip, especially when they are planting corn-on-corn. Adding crop diversity through cover crops is another strategy Martin uses in their crop rotation.

The operation seeds 30-35 pounds per acre of a variety of cover crop mixes:

- Balansa clover, barley, African cabbage

- Balansa clover, Austrian winter peas, radish, buckwheat, oats

- Balansa clover, peas, buckwheat, African cabbage, oats

- Turnip, rapeseed, vetch, Austrian winter peas, Ladino clover, kale, oats

- Oats and Ladino clover

Ahead of planting soybeans, Martin likes to seed 60-70 pounds of cereal rye per acre.

“We use a crop rotation of 2 years of corn and 1 year of early-planted soybeans,” he says. “We seed the crimson clover with a [Great Plains] Turbo Till and broadcast the oats and clover.

“Planting early soybeans allows us to harvest them earlier and get a better jump on planting cover crops. We’ve been using covers on a large-scale basis for 5-6 years, and we are still in the process of learning exactly just which combinations work better for us.”

Although Martin says he likes using annual rye and rapeseed — which have a more extensive root system — the cereal rye has been easier for their operation to control. He says they even planted into mature cereal rye, which turned out very well.

Since aerial seeding has not been successful for Martin, the operation seeds covers with a Gandy seeder on a TurboMax. With the push to plant soybeans earlier, they have created some strips in corn stalks in the fall where beans will be planted next spring, fashioning a better seedbed for early planting.

“We’re experimenting, throwing in different mixes to see what works,” he says. “We look at different soils and try to figure out if there’s one cover crop that’s better than another for the soil biology.”

Martin prefers to have fall cover crops planted by September 15.

“We plant cover crops in the fall using the Turbo Till, an Orthman DR series planter and a John Deere tracked tractor outfitted with stalk stompers,” he says. “We feel the planter gives us a real advantage, because it holds 40 bushels and air vacuums out, broadcasting ahead of the Turbo Till, which works the seed in a little bit.

“The yield potential and genetic potential on a corn plant is 1,100 bushels in a perfect environment. Just because I can make 300 bushels does not mean that is my maximum profit…”

“We haven’t yet figured out how to get all our acres covered to get enough growth in the season to benefit us. We’ve been planting about 30% of our acres with cover crops for 5 years, and we feel that is an important step in the process to improving soil health.”

Martin says they have tried using aerial application to seed covers but struggled to seed them into 30-inch soybean rows.

“It seems like we get them established, and then it gets dry,” he says. “The soil didn’t hold the moisture, so the covers died. Planting covers into corn has worked a little bit better.”

“We have had pretty good weed control with covers,” he says. “We also need to study leaving the Ladino clover and not killing it until the second pass with chemicals and see what advantage we had.

“We had hairy vetch and rapeseed that did not get killed with our first chemical pass of Roundup. It was the best corn we had on the farm that year. We got it under control with our second pass of chemical.”

Post a comment

Report Abusive Comment